🎓 89/2

This post is a part of the Natural language processing educational series from my free course. Please keep in mind that the correct sequence of posts is outlined on the course page, while it can be arbitrary in Research.

I'm also happy to announce that I've started working on standalone paid courses, so you could support my work and get cheap educational material. These courses will be of completely different quality, with more theoretical depth and niche focus, and will feature challenging projects, quizzes, exercises, video lectures and supplementary stuff. Stay tuned!

Topic modeling remains one of the most prominent unsupervised learning techniques used to automatically infer the hidden thematic structure from large collections of documents. While originally devised for textual data, it has also been extended to a variety of domains such as bioinformatics, image processing (where "topics" can represent clusters of visual features), or event detection in social networks. The overall motivation stems from the desire to discover latent factors or hidden topics that shape the content of a corpus. These latent factors in text usually manifest themselves as sets of terms that frequently co-occur together — revealing emergent themes that an analyst might not have previously anticipated.

Topic modeling enables researchers, data scientists, and domain experts to drastically reduce the complexity of large textual archives. Instead of manually reading thousands (or millions) of documents, one can employ topic modeling to group documents by high-level themes. This has found wide application in:

- Content recommendation systems: A news website or a blog aggregator might use topic modeling to categorize articles, surface them to relevant audiences, and suggest thematically related stories.

- Academic research: Digital humanities scholars utilize topic modeling to explore large bodies of literature or historical archives, gleaning patterns across centuries of texts, and discovering how themes have evolved.

- Market research and brand monitoring: Social media content, customer feedback, or product reviews can be studied to find recurring topics or sentiments. Topic modeling helps to cluster these texts into marketing-relevant themes (for instance, design features, shipping problems, pricing concerns).

- Search and indexing: Topic models can be used to index documents more efficiently, so that searching by topic yields more relevant results than naive keyword-based retrieval.

- Trend analysis in social networks: Online communities often generate textual content at astonishing velocity. Topic modeling can be applied to identify trending topics, reveal emergent phenomena, or detect changes in discourse over time.

- Fraud detection and security: In certain contexts, textual logs (like emails, chat transcripts, or security logs with textual descriptions) might contain hidden patterns. Topic models may reveal suspicious themes or patterns that signal fraud or illicit behavior.

- Medical and biomedical research: Clinical notes, scientific publications in medicine, and patient feedback can be massive in scale. Topic modeling helps cluster key areas of concern and could even highlight previously overlooked subtopics.

In sum, topic modeling is a powerful lens through which textual data can be reinterpreted. The automatically extracted topics serve as an abstraction or compressed representation of the text, helping us to handle, navigate, and conceptualize immense corpora more effectively.

Chapter 2. Foundational concepts

Latent variables in text modeling

In most topic modeling approaches, the notion of "latent variables" is central. A latent variable is a hidden or unobserved variable that influences the observed data. In text modeling, each document is assumed to be generated by a mixture of underlying topics — topics themselves are distributions over words or terms. The intensities or probabilities with which topics appear in a document are these latent variables that we attempt to infer.

For instance, suppose you have a large collection of news articles about world events, sports, politics, technology, and the arts. Each article is formed by certain combinations of these topic distributions (latent variables). If you find a document with 50% focus on technology, 20% on business, 20% on politics, and 10% on sports, that is effectively a set of inferred latent variables describing the composition of that document. The presence of these hidden factors is not directly observable but can be inferred through statistical means.

Probability distributions and their role in topic modeling

Topic modeling frameworks usually adopt a probabilistic generative perspective. In the classic generative story of Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) — which we will discuss more thoroughly soon — each topic is represented by a probability distribution over words from the vocabulary. Likewise, each document is represented by a distribution over topics. Mathematically, you might see the topic distribution for document denoted as (a vector of probabilities summing to 1), and the word distribution for topic denoted as .

Then, if we pick a particular word from document , we do so by first choosing a topic with probability and then choosing a particular word from the distribution over words for that topic . Formally, you might see something along the lines of:

Where:

- is the total number of topics.

- is the probability that topic is chosen when generating a word from document .

- is the probability of word under topic .

Hence, each topic is defined as a distribution over words, and each document is defined as a distribution over topics. This perspective allows the data scientist to exploit the entire probabilistic machinery (e.g., Bayesian inference, maximum likelihood approaches, variational inference, or Gibbs sampling) to estimate these latent variables.

Dimensionality reduction and its connection to topic modeling

Topic modeling can be viewed as a form of dimensionality reduction. A given corpus of documents can be extremely high-dimensional if we consider each unique word as a dimension. Suppose your vocabulary has words, then each document is nominally represented as a point in a -dimensional space (e.g., as a bag-of-words vector). However, in a topic model with latent topics, each document is effectively captured by a -dimensional representation: its topic mixture distribution. Thus, the raw dimensionality is reduced to , while hopefully retaining most of the semantic content.

In that sense, topic modeling is loosely analogous to other matrix factorization or decomposition techniques such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or Non-negative Matrix Factorization (NMF). However, the difference in most topic modeling approaches is the explicit probabilistic interpretation: each dimension in the reduced space (i.e., each topic) is a probability distribution over words rather than a purely algebraic factor.

Terminology of topic modeling

Some commonly encountered terms in topic modeling:

- Topic: A probabilistic distribution over the vocabulary that tends to reflect a coherent theme (e.g., sports, politics, or technology).

- Topic mixture: The distribution over the set of topics for a specific document. Usually denoted as in many topic modeling frameworks.

- Word distribution: For each topic, we have a distribution over words, typically denoted or sometimes .

- Hyperparameters: These are parameters controlling the shape of the distributions over topics and words (e.g., alpha and beta in LDA).

- Variational inference / Gibbs sampling: Algorithms used in some topic models to perform inference and find the posterior distribution of latent variables.

Topic modeling frameworks vary in how they formulate the relationships among these components, but the above terms tend to remain consistent across many methods.

Chapter 3. Popular topic modeling frameworks

Topic modeling has evolved to encompass an array of frameworks and paradigms, each with unique strengths, assumptions, and computational complexities. Below are some of the most commonly used:

Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA)

Latent Dirichlet Allocation (Blei, Ng, & Jordan, JMLR 2003) is probably the most well-known method of topic modeling. LDA introduced a fully generative Bayesian model for documents. The name "Dirichlet" arises from the prior placed over the per-document topic distribution and the per-topic word distribution.

- Generative process:

- For each document , draw a distribution over topics from a Dirichlet prior with parameter .

- For each topic , draw a distribution over words from a Dirichlet prior with parameter .

- For each word in a document, choose a topic assignment according to , then choose a word according to .

A commonly used formula for the joint distribution of the latent variables and observed words in LDA is:

Where:

- is the number of documents.

- is the number of words in document .

- is the number of topics.

- and are hyperparameters for the Dirichlet priors.

- is the distribution of topics in document .

- is the distribution over words for topic .

- is the topic assignment for the -th word in document .

- is the actual observed word.

Inference for LDA can be done with Gibbs sampling, variational inference, or other approximate methods. Although LDA can be computationally expensive, it remains a standard reference due to its interpretability and strong theoretical grounding.

Probabilistic latent semantic analysis (PLSA)

Probabilistic Latent Semantic Analysis (Hofmann, 1999) can be viewed as a precursor to LDA. It also models documents in terms of latent topics, but it lacks a prior over topic distributions and is thus considered a non-Bayesian approach. Instead, it relies on a maximum likelihood estimation with an Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithm to find the parameters.

A key difference from LDA is that PLSA can overfit, especially because it introduces a large number of parameters without having a proper prior. LDA, by contrast, introduces Dirichlet priors that control the distributions and reduce overfitting. Despite this, PLSA is still used in certain contexts and provides a simpler conceptual introduction to how text can be factorized into latent topics.

Non-negative matrix factorization (NMF)

Non-negative matrix factorization is a purely algebraic approach to factor a term-document matrix into two lower-rank matrices, both of which have only non-negative entries. If is a matrix representing word counts (or TF-IDF scores) of words across documents, NMF attempts to find two matrices (size ) and (size ) such that:

Here, is the reduced rank — often analogous to the number of topics. If is interpreted as containing basis vectors (topics) and as document loadings, each column of tells us how strongly a topic appears in a document. The non-negativity constraint makes the factorization more interpretable compared to, say, SVD-based methods like Latent Semantic Analysis (LSA).

NMF is frequently used as a faster approach compared to LDA, though it does not have a fully probabilistic interpretation. However, in practice, it can yield coherent topics that are relatively easy to interpret, especially because it keeps the weighting of words and topics strictly positive.

Hierarchical Dirichlet processes (HDP)

Hierarchical Dirichlet Processes (Teh and gang, 2006) generalize the LDA concept to a scenario where we do not fix the number of topics in advance. Instead, the model can discover an appropriate number of topics automatically, guided by the data. This is done through a hierarchical Bayesian construction known as the Dirichlet process. Essentially, the model treats as infinite in principle, but in practice the posterior distribution typically places most probability mass on a finite set of topics.

HDP is very appealing for large corpora where you might be uncertain about the number of distinct themes. It lets the data guide how many topics are discovered. The trade-off is that inference becomes more sophisticated, often involving specialized MCMC approaches or variational methods. Also, HDP can sometimes discover more topics than are practically interpretable, so it's not always a silver bullet.

Dynamic topic models

Dynamic topic models (Blei & Lafferty, ICML 2006) address the evolution of topics over time. Traditional LDA presumes that each document is exchangeable (i.e., no temporal ordering). But in many domains, documents come with timestamps, and the themes may shift over months or years. For example, the vocabulary around "technology" changes significantly over decades, as the popular jargon shifts from mainframe computing to cloud computing to machine learning.

Dynamic topic models incorporate temporal dependencies by indexing the latent distributions on discrete time slices. A typical approach is to model the topics at time slice as evolved from the topics at time slice . This is often achieved via state space models or Brownian motion in the parameter space of the distributions. This allows the model to capture how word probabilities shift over time for each topic, providing a chronological storyline of how certain themes appear, evolve, and potentially vanish.

Chapter 4. Steps in building a topic model

Data collection and corpus preparation

The first step in building any topic model is collecting the relevant text data. The data could come from web pages, academic journals, social media posts, news articles, or specialized corporate documents. Frequently, large-scale corpora are stored as sets of text files or in a database. The typical tasks in this phase include:

- Gather documents: Make sure you have well-labeled or at least organized data sources.

- Ensure coverage: If the corpus is supposed to capture a wide range of topics, you need a sufficiently broad variety of texts.

- Remove duplicates: Check for repeated documents or near-duplicates that might bias the model.

Also, keep in mind the final application: if you are building a specialized model for, say, social media data, you want to ensure your corpus is representative of relevant user posts, not just random data that might not reflect your end goals.

Data preprocessing: text cleaning, tokenization, stopword removal and filtering, stemming vs. lemmatization

Textual data is often noisy or inconsistent, especially if it is scraped from the web or user-generated. Proper preprocessing typically involves:

- Text cleaning: Convert text to a consistent casing (often lowercase), remove non-alphanumeric characters (or decide how to handle them), handle punctuation, convert numbers or keep them if relevant.

- Tokenization: Split the text into tokens, typically words or subwords. Tokenizers in languages like Python (NLTK, spaCy) provide robust ways to handle this.

- Stopword removal: Many words (like "the", "is", "and", etc.) appear frequently but do not hold strong semantic content. Common practice is to remove them if your topic modeling approach focuses on content words.

- Stemming or lemmatization: Reduce words to their root form. Stemming is a rule-based approach that chops off word endings ("organization" → "organiz") whereas lemmatization uses morphological analysis to map words to their actual lemma forms ("feet" → "foot", "organized" → "organize"). Lemmatization typically yields more coherent topics but is computationally heavier.

- Filtering by token length or frequency: It may be beneficial to remove extremely rare words that appear in only a handful of documents, as well as overly frequent words that appear in almost every document.

These steps can dramatically affect the quality of your topic model. Preprocessing transformations might remove noise and help the model focus on semantically meaningful content.

Model training

Once you have a clean corpus and you have decided on a specific approach (e.g., LDA, NMF, HDP, etc.), the next step is to train the model. For LDA, you might use:

- Gensim in Python, which offers an efficient implementation of online LDA.

- MALLET (a Java-based library) for topic modeling, which uses an optimized Gibbs sampler.

- Scikit-learn for simpler, smaller-scale LDA or NMF.

In a typical workflow, you do something like:

from gensim import corpora, models

from gensim.utils import simple_preprocess

# Suppose you already have tokenized_texts: a list of lists of tokens

dictionary = corpora.Dictionary(tokenized_texts)

dictionary.filter_extremes(no_below=5, no_above=0.5)

bow_corpus = [dictionary.doc2bow(text) for text in tokenized_texts]

lda_model = models.LdaModel(

bow_corpus,

num_topics=20,

id2word=dictionary,

passes=10,

alpha='auto',

random_state=42

)

# Inspect the topics

topics = lda_model.print_topics(num_words=5)

for topic_id, topic_words in topics:

print(f"Topic {topic_id}: {topic_words}")

This snippet demonstrates a typical approach to training an LDA topic model with Gensim. The LdaModel constructor requires a bag-of-words representation , a chosen number of topics, the dictionary mapping, and other hyperparameters. The specific arguments can vary based on dataset size, interpretability requirements, and computational resources.

Selecting hyperparameters

In LDA, there are several hyperparameters that can significantly influence the outcome:

- Number of topics (): Possibly the most important parameter. In practice, domain knowledge or interpretability concerns guide the choice of .

- Alpha (): The Dirichlet parameter that controls document–topic sparsity. A lower alpha typically yields more sparse distributions (each document is dominated by fewer topics).

- Beta ( or sometimes referred to as ): The Dirichlet parameter that controls topic–word sparsity. A lower beta means topics focus on fewer words.

- Number of passes / iterations: Controls how many times the training algorithm iterates over the corpus. More passes can improve convergence but cost additional runtime.

In frameworks like HDP, there may be extra parameters controlling the base distribution of topics and the concentration parameters that govern how many new topics are introduced. NMF likewise has parameters for the rank and different update rules (e.g., multiplicative updates, coordinate descent).

Ensuring model convergence

Different inference algorithms have different stopping criteria and convergence diagnostics. For example:

- Gibbs sampling might run for a specified number of iterations, after which the model's state is hopefully close to stationary. One can monitor log-likelihood or use heuristics to decide how many iterations are enough.

- Variational inference can track the Evidence Lower BOund (ELBO), stopping when improvement becomes negligible.

- EM algorithm (for PLSA) might track the change in log-likelihood from one iteration to the next.

In practical scenarios, you also look at the stability of the resulting topics. If the top words in each topic keep shifting drastically between iterations, the model might not have converged yet.

Evaluating training progress

During training, it's common to observe metrics like the held-out perplexity or the likelihood of a validation set, or simply to look at the topic-word distributions qualitatively. Tools like pyLDAvis are often used to visually inspect how topics are laid out in a two-dimensional representation (via multidimensional scaling). If training is going well, you tend to see well-separated topics in the visualization, each with a fairly coherent cluster of words.

Model evaluation

Evaluating topic models is notoriously tricky because there is no ground-truth label for what a "good" topic is in many real-world data sets. Nonetheless, several strategies exist:

Topic coherence metrics

Topic coherence metrics (Mimno and gang, 2011) aim to quantify how semantically coherent the top words of a topic are. Common metrics include:

- C_v: A popular approach that uses word co-occurrence counts and a sliding window to measure coherence.

- C_uci, C_umass: Based on pointwise mutual information (PMI).

- NPMI: Normalized pointwise mutual information-based metric.

Coherence scores are used heavily in practice to select the optimal number of topics , or to compare different variants of a model.

Perplexity and likelihood-based metrics

In the language modeling tradition, perplexity is sometimes used to measure how well a probabilistic model predicts a held-out set of documents. A lower perplexity indicates a better predictive model of text. However, perplexity can be somewhat misleading because an overly complex model can overfit, driving perplexity down but not necessarily providing more interpretable topics.

Human evaluations and qualitative checks

In many practical scenarios, the final judge of a topic model is a domain expert. Does the topic's top words make sense as a coherent theme? Does the model separate distinct topics into separate clusters, or are multiple themes merged or split incorrectly?

Human-based evaluation is time-consuming, but it provides the ultimate test of interpretability, which is often the main goal of topic modeling.

Model interpretation and visualization

The real power of topic modeling comes in interpreting the discovered topics and applying them to the original corpus. Key tasks include:

- Examining topic–word distributions: Inspect the top words and their probabilities for each topic. Sometimes you might label the topic based on the top words.

- Topic labeling techniques: Automated techniques can be used to assign descriptive labels to each topic. For example, you can see which words appear frequently in that topic, or examine the most representative documents. Alternatively, some approaches (Mei and gang, 2007) propose using bigrams or salient phrases to label topics more precisely.

- Visualizing topics: Tools like pyLDAvis or custom embeddings-based plots (e.g., projecting topics into a 2D space) help you see how topics relate to each other and to the documents.

- Document–topic distributions: You can examine which topics are prevalent in each document, or how topics are distributed across different subsets of the corpus.

Visualization tools and libraries

- pyLDAvis: A popular Python library for interactive topic model visualization.

- Gensim's built-in visualization: Some basic plot functions exist, though typically one uses pyLDAvis.

- Word cloud: Some practitioners generate word clouds from the top words for each topic.

- Gephi or other graph-based tools: Sometimes used if you represent topics as networks of words.

Interpreting the output in these ways can provide valuable insights, especially for business intelligence or academic research where clarity is paramount.

Chapter 5. Advanced techniques and variations

Neural topic modeling

Recently, neural topic modeling has gained momentum, aiming to leverage deep neural networks (often autoencoders or variational autoencoders, VAEs) to discover topics in text. Methods like ProdLDA (Srivastava & Sutton, 2017) re-parameterize the distribution over topics using neural networks, attempting to address some limitations of traditional LDA. The deep generative perspective can:

- Better capture non-linear text representations.

- Integrate with word embeddings or other neural features.

- Potentially scale to massive datasets using GPU acceleration.

Despite these benefits, neural topic models may introduce new complexities in training (e.g., optimizing VAE objectives, balancing reconstruction vs. KL divergence) and might require more hyperparameter tuning.

Combining topic modeling with word embeddings

Classic topic models treat words largely as discrete tokens, ignoring possible semantic similarities between them (for instance, synonyms). By combining topic modeling with word embeddings (e.g., Word2Vec, GloVe, or fastText), it becomes possible to produce topics that incorporate distributional semantics. Some approaches:

- Top2Vec (Angelov, 2020): Leverages document embeddings and then clusters them, effectively discovering topic embeddings.

- Embedding-based coherence: You can use word embedding similarities to measure how coherent a topic's words are, providing a more nuanced evaluation.

This synergy can produce topics that are more robust to synonyms or polysemy. On the downside, it adds another layer of complexity to the pipeline and can require a large, high-quality embedding model.

Deep learning approaches for topic modeling

Beyond straightforward neural topic modeling, there is a whole ecosystem of deep learning solutions that incorporate attention mechanisms, Transformers, or graph-based neural networks to glean more contextual or structural information from text:

- Transformer-based encoders: They can be used to generate rich contextual embeddings for tokens or entire sentences, potentially leading to refined topic representations.

- Graph neural networks: In specialized domains where the text might also be linked or references are crucial (e.g., scientific citation networks), GNN-based models can incorporate topological information.

Although these approaches can be powerful, they also come at a higher computational cost and often require carefully engineered architectures.

Cross-lingual topic modeling

Cross-lingual topic modeling addresses the scenario where you have documents in multiple languages and you want to discover overarching topics that span those languages. This can be approached by:

- Sharing a common latent space for topics, with separate word distributions for each language.

- Using bilingual word embeddings or multi-lingual representations so that synonyms across languages can align into a single topic dimension.

Such models are highly relevant in globally oriented text analytics, especially for multinational companies, cross-lingual search engines, or multilingual social media analysis.

Ensemble methods for topic discovery

Ensemble approaches can also be employed for topic modeling:

- Multiple random initializations: Running LDA multiple times with different seeds and combining or merging similar topics to yield more stable solutions.

- Combining multiple methods: For example, using NMF to get an initial sense of topics, then refining those topics via an LDA-based approach. Or you can run LDA with different hyperparameters and ensemble the discovered topics if you find them complementary.

Ensemble methods may enhance robustness and produce well-rounded sets of topics that capture different aspects of the corpus.

Chapter 6. Let's code

Building complex topic model from scratch

In this final section, I will illustrate how you can build a more involved topic modeling pipeline in Python. Rather than just showing the typical Gensim snippet, we will aim to demonstrate the entire pipeline, complete with preprocessing, training, and evaluation of a topic model (such as LDA or NMF), along with a quick demonstration of how to visualize topics with pyLDAvis.

Step 1: Data ingestion and cleanup

Let's suppose we have a dataset of documents stored in a file or database. We'll do a simplified illustration:

import pandas as pd

import re

from nltk.corpus import stopwords

from nltk.stem import WordNetLemmatizer

from gensim.utils import simple_preprocess

stop_words = set(stopwords.words('english'))

lemmatizer = WordNetLemmatizer()

def preprocess_text(text):

# Lowercase

text = text.lower()

# Remove some non-alphanumeric characters (for demonstration)

text = re.sub(r'[^a-z0-9s]', '', text)

# Tokenize

tokens = simple_preprocess(text, deacc=True) # deacc=True removes punctuations

# Remove stopwords and lemmatize

filtered_tokens = []

for tok in tokens:

if tok not in stop_words:

lemma = lemmatizer.lemmatize(tok)

filtered_tokens.append(lemma)

return filtered_tokens

# Suppose we load a CSV with a column 'text'

df = pd.read_csv('documents.csv')

df['processed'] = df['text'].apply(preprocess_text)

Here, we do some minimal cleaning, tokenization, stopword removal, and lemmatization. In a real scenario, you might do more sophisticated text normalization.

Step 2: Building a dictionary and corpus

Next, we convert the processed tokens into a bag-of-words representation:

from gensim import corpora

dictionary = corpora.Dictionary(df['processed'])

dictionary.filter_extremes(no_below=5, no_above=0.4) # example thresholds

bow_corpus = [dictionary.doc2bow(doc) for doc in df['processed']]

We have also used filter_extremes to remove very rare words (appear in fewer than 5 documents) and extremely common words (appear in more than 40% of documents). Adjust these thresholds depending on your data size and domain knowledge.

Step 3: Training an LDA model

Now, we can train an LDA model using Gensim's LdaModel or LdaMulticore (for parallelization):

from gensim.models.ldamodel import LdaModel

num_topics = 10 # Choose your number of topics

lda_model = LdaModel(

corpus=bow_corpus,

id2word=dictionary,

num_topics=num_topics,

random_state=42,

passes=10,

alpha='auto'

)

# Print out the topics

for idx, topic in lda_model.print_topics(num_words=5):

print(f"Topic {idx}: {topic}")

Here, we have set the number of topics to 10, but you would typically try a range (like 5, 10, 15, 20, etc.) and pick the best number based on your chosen evaluation method (coherence, perplexity, or domain feedback).

Step 4: Evaluating with topic coherence

Gensim has built-in coherence measures:

from gensim.models import CoherenceModel

coherence_model_lda = CoherenceModel(

model=lda_model,

texts=df['processed'],

dictionary=dictionary,

coherence='c_v'

)

coherence_lda = coherence_model_lda.get_coherence()

print(f'Coherence Score (c_v): {coherence_lda}')

You can also choose 'u_mass' or 'c_uci' if you have the necessary reference corpus or prefer those metrics. A higher coherence usually indicates more interpretable topics, although interpretation is still somewhat subjective.

Step 5: Visualizing with pyLDAvis

An optional but highly recommended step is to visualize your topics:

import pyLDAvis

import pyLDAvis.gensim_models as gensimvis

pyLDAvis.enable_notebook() # if you're in a notebook

vis_data = gensimvis.prepare(lda_model, bow_corpus, dictionary)

pyLDAvis.save_html(vis_data, 'lda_visualization.html')

This produces an interactive visualization showing the relationships between topics and the top terms in each topic. You can open the resulting "lda_visualization.html" to hover over different circles (representing topics) and see the word distributions.

Step 6: Trying NMF as an alternative

Sometimes, you might find that NMF is more straightforward or runs faster:

from sklearn.feature_extraction.text import TfidfVectorizer

from sklearn.decomposition import NMF

# Convert documents to TF-IDF matrix

tfidf_vectorizer = TfidfVectorizer(

min_df=5,

max_df=0.4,

stop_words='english'

)

tfidf_matrix = tfidf_vectorizer.fit_transform(

[' '.join(doc) for doc in df['processed']]

)

# Train NMF

num_topics = 10

nmf_model = NMF(n_components=num_topics, random_state=42)

W = nmf_model.fit_transform(tfidf_matrix)

H = nmf_model.components_

# Display top words for each topic

terms = tfidf_vectorizer.get_feature_names_out()

for topic_idx, topic_vec in enumerate(H):

top_indices = topic_vec.argsort()[:-6:-1] # top 5

top_terms = [terms[i] for i in top_indices]

print(f"Topic {topic_idx}: {', '.join(top_terms)}")

While not probabilistic, NMF can be a very fast and intuitive approach, especially for exploring your data quickly.

Throughout these steps, you may incorporate advanced variations such as hierarchical approaches or dynamic topic modeling if your data is time-stamped. For more advanced neural methods, frameworks like PyTorch or TensorFlow are used to build the neural architecture for a topic model, often requiring additional custom code.

Remember that real-world text analytics workflows often involve:

- Larger corpora that require distributed solutions (like Spark or HPC clusters).

- More nuanced text cleaning, domain-specific tokenization or phrase detection.

- Ongoing iteration of topic number selection and hyperparameter tuning.

- Detailed interpretability checks with domain experts.

Finally, it's beneficial to combine computational metrics (like coherence or perplexity) with human feedback. Topic modeling is inherently interpretive: you want topics that not only fit the data statistically but also make sense to people who will use those insights for further decision-making.

An image was requested, but the frog was found.

Alt: "Topic model diagram"

Caption: "A conceptual diagram of a topic model illustrating a set of documents being mapped onto latent topics. Each topic is a distribution over terms, and each document is a distribution over topics."

Error type: missing path

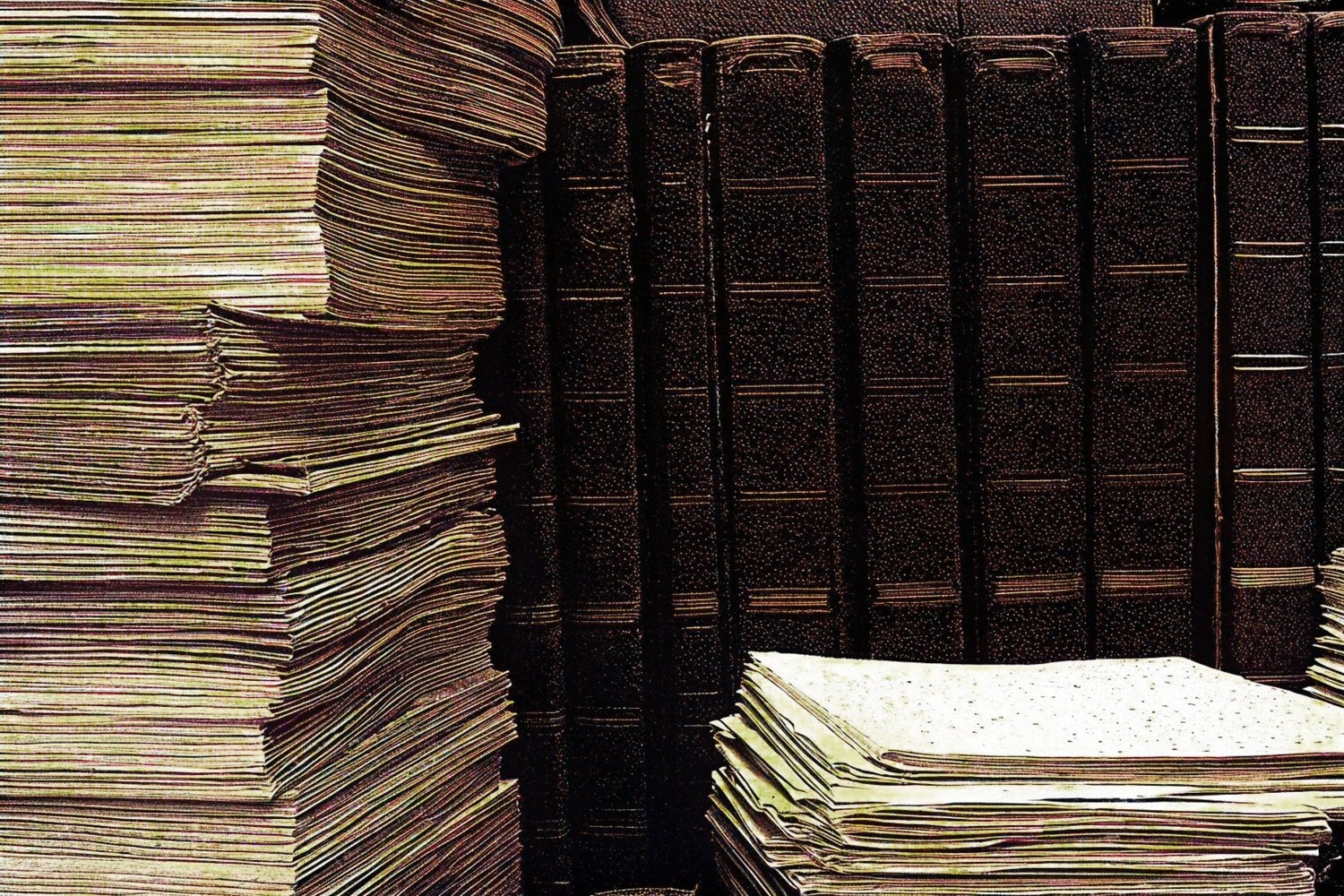

An image was requested, but the frog was found.

Alt: "Dynamic topic model illustration"

Caption: "Visualization of how topics change over time in a dynamic topic model. Each color-coded topic evolves to reflect new words or shifting probabilities."

Error type: missing path

This concludes the detailed exploration of topic modeling. By engaging with fundamental ideas (latent variables, probability distributions, dimension reduction) and advanced concepts (hierarchical Dirichlet processes, neural topic modeling, cross-lingual topic discovery), topic modeling can be adapted to a wide range of practical text analytics scenarios. The final code examples illustrate a typical pipeline — starting with data ingestion, preprocessing, model training, evaluation, and visualization — which can be extended or combined with new innovations in the field.