🎓 8/168

This post is a part of the Mathematics educational series from my free course. Please keep in mind that the correct sequence of posts is outlined on the course page, while it can be arbitrary in Research.

I'm also happy to announce that I've started working on standalone paid courses, so you could support my work and get cheap educational material. These courses will be of completely different quality, with more theoretical depth and niche focus, and will feature challenging projects, quizzes, exercises, video lectures and supplementary stuff. Stay tuned!

Discrete distributions

Bernoulli distribution

The Bernoulli distribution is the simplest discrete distribution, describing a single binary trial that can yield either "success" () with probability or "failure" () with probability . The probability mass function (pmf) is:

- Support:

- Parameters: success probability

- Skewness & kurtosis: for , the distribution is skewed; it becomes symmetric at . Kurtosis can be relatively high because the distribution is concentrated on two points.

- Use cases: The Bernoulli distribution is at the core of binary classification labels in machine learning. It is often used to model success/failure processes such as "clicked/not clicked" in online advertising.

- Parameter estimation: The maximum likelihood estimator (MLE) for is the sample mean of the observed successes. For instance, if you observe trials with successes, the MLE is .

An image was requested, but the frog was found.

Alt: "Bernoulli pmf"

Caption: "A simple Bernoulli pmf with different values of p."

Error type: missing path

Binomial distribution

A Binomial distribution describes the number of successes in a fixed number of independent Bernoulli trials, each with probability of success . Its pmf is:

- Support:

- Parameters: number of trials , success probability

- Mean & variance: and

- Skewness:

- Use cases: Frequently used in data science for modeling counts of occurrences across multiple trials, such as the number of customers who respond to a campaign out of recipients.

- Parameter estimation: The MLE approach again yields , where is the total number of binomial experiments (if data come in aggregated form). If you have separate sequences of trials, you typically estimate as the overall fraction of successes.

An image was requested, but the frog was found.

Alt: "Binomial pmf"

Caption: "Example binomial distribution with n=10, p=0.3 and n=10, p=0.7."

Error type: missing path

Poisson distribution

The Poisson distribution is used for modeling the number of events occurring in a fixed interval, assuming events happen with a known constant mean rate and independently of the time since the last event. Its pmf is:

- Support:

- Parameter: rate (> 0)

- Mean & variance:

- Skewness & kurtosis: Skewness decreases as grows, but it remains right-skewed.

- Use cases: Modeling counts of rare or random events, e.g., number of arrivals in a queue, number of network requests in a given time frame.

- Parameter estimation: The MLE for is the sample mean of observed counts.

One interesting property is that if and are independent, then is .

Geometric distribution

A Geometric distribution models the number of trials needed to get the first success (or, in another convention, the number of failures before the first success). We'll use the "number of trials" version. Its pmf is:

- Support:

- Parameter: success probability

- Mean & variance: ,

- Memoryless property: The probability of success in future trials is independent of the number of failures so far.

- Use cases: Modeling discrete "waiting time" until an event occurs, such as how many times you must roll a die before seeing a certain face.

- Parameter estimation: The MLE for is , where is the sample mean of the observed counts until first success.

Negative binomial distribution

The Negative binomial distribution can be viewed as the number of successes before a specified number of failures is reached, or as a sum of a fixed number of geometric random variables. One popular parametrization (the number of successes before failures) has the pmf:

- Parameters: (the number of failures) and (success probability)

- Mean & variance: ,

- Use cases: Particularly useful when the variance in the data exceeds the mean (overdispersion), unlike the Poisson distribution. Common in modeling number of successes in real-world count processes, e.g., number of insurance claims before a threshold of losses is reached.

- Parameter estimation: Methods include MLE and method of moments. Overdispersion can make direct estimation trickier than Poisson. Specialized software functions are often used.

Multinomial distribution

A Multinomial distribution generalizes the binomial to more than two possible outcomes. If each trial can result in one of categories, with probabilities (summing to 1), and you perform independent trials, the probability of observing counts is:

subject to .

- Support: Nonnegative integer vectors of dimension summing to

- Parameters: number of trials , probability vector

- Mean & covariance: ; covariances depend on both and

- Use cases: Modeling the counts of outcomes across multiple categories, e.g., how many times each side of a die shows up in rolls.

- Parameter estimation: The MLE for is the fraction of observations falling into category : .

Categorical distribution

The Categorical distribution is to the multinomial what the Bernoulli is to the binomial. It's a single trial that results in exactly one of categories, with probabilities . The pmf for outcome is:

, where .

- Support:

- Parameters: probability vector

- Use cases: Class labels in multi-class classification, or any scenario with a single trial and multiple possible outcomes.

- Parameter estimation: The MLE is again the empirical relative frequency for each category.

Continuous distributions

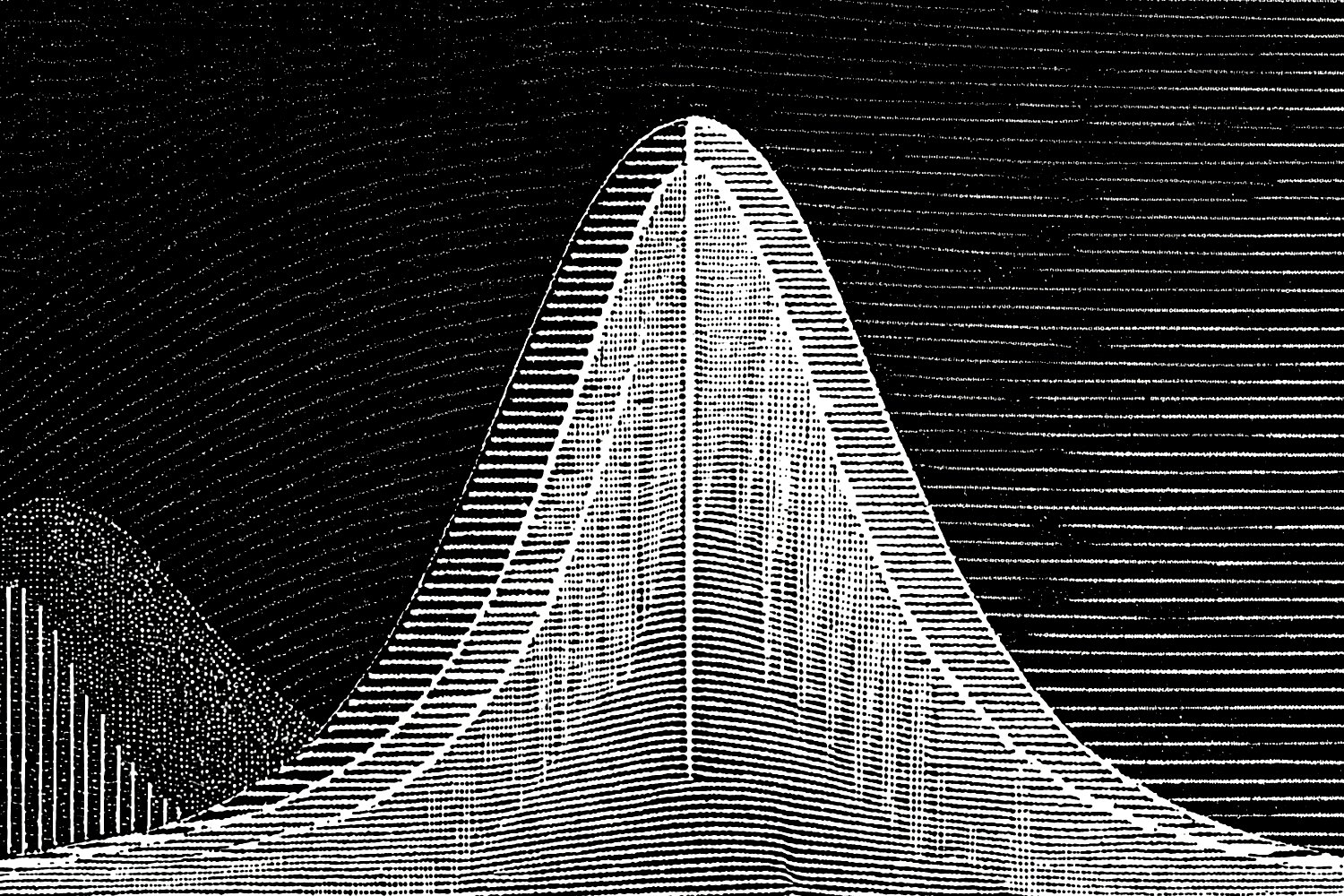

The gaussian (normal) distribution in-depth

The Gaussian distribution (also known as the Normal distribution) is one of the most important continuous distributions in statistics and machine learning due to the central limit theorem and its convenient analytical properties. Its probability density function (pdf) for a variable is:

where:

- is the mean (location parameter).

- is the standard deviation (scale parameter).

Key properties:

- Symmetry & shape: Perfectly symmetrical around .

- Support:

- Mean & variance: and

- Conditional and marginal distributions: Any linear combination (or conditional distribution) of jointly normal variables is also normally distributed.

- Bayes' theorem for Gaussian variables: Gaussian distributions serve as conjugate priors in many Bayesian inference scenarios, making posterior distributions also Gaussian.

- Maximum likelihood: The MLE estimates are the sample mean and sample variance for and respectively.

- Sequential estimation: With each new observation, one can update the sample mean and variance incrementally. In a Bayesian context with a Gaussian prior, the posterior is still Gaussian.

- Periodic variables: If data are truly periodic (like angles), simply using a normal distribution may lead to inaccuracies, because normal distributions ignore wraparound effects.

An image was requested, but the frog was found.

Alt: "Gaussian pdf"

Caption: "Normal distributions with different means and variances."

Error type: missing path

The exponential distribution and the exponential family

The exponential distribution is a core member of the broader exponential family of distributions (which also includes Bernoulli, Poisson, Gamma, and more). Focusing on the exponential distribution itself:

- Support:

- Parameter: rate

- Mean & variance:

- Memoryless property: The exponential distribution is continuous-time analog of the geometric distribution's memorylessness.

- Use cases: Time between events in a Poisson process, reliability analysis, survival analysis.

- Parameter estimation: The MLE for is , where are the observed waiting times.

Conjugate and noninformative priors

- Conjugate priors: In Bayesian inference, the gamma distribution is a conjugate prior for of an exponential distribution. This means the posterior remains gamma-distributed after observing data.

- Noninformative priors: Sometimes, a Jeffreys prior (

A Jeffreys prior is derived to be invariant under reparameterization and often used when we have little prior knowledge.), which is proportional to the square root of the Fisher information, is used when no strong prior beliefs are held.

Gamma distribution

The Gamma distribution generalizes the exponential by allowing an additional shape parameter . One parametrization is:

(Here is the gamma function, not to be confused with a random variable.)

- Support:

- Parameters: shape , rate (sometimes scale is used)

- Mean & variance:

- Relation to exponential: The exponential is a special gamma with .

- Use cases: Modeling waiting times, reliability analysis, sum of exponential variables. If events follow a Poisson process, then the waiting time for the -th event is gamma-distributed.

- Parameter estimation: Common methods include MLE or method of moments. MLE typically requires numerical optimization (e.g., using Newton-Raphson).

Beta distribution

Defined on , the Beta distribution is a versatile choice for modeling probabilities or proportions. Its pdf is:

where is the beta function (normalizing constant).

- Support:

- Parameters: shape parameters

- Mean & variance: ,

- Use cases: Particularly important in Bayesian inference as conjugate priors for the Bernoulli/binomial parameters; also used in modeling distributions of proportions in a population.

- Parameter estimation: The MLE or method of moments can be used. Bayesian updates for and are very common in posterior inference for unknown probabilities.

Chi-square distribution

A chi-square distribution with degrees of freedom is the distribution of a sum of squared independent standard normal variables. Its pdf is:

- Support:

- Parameter: degrees of freedom

- Mean & variance: ,

- Use cases: Commonly used in hypothesis testing (chi-square tests), confidence intervals for variance, and other inferential procedures in statistics.

- Parameter estimation: Usually arises as a derived distribution from normal assumptions, rather than from direct fitting. However, method-of-moments can be applied if needed.

Student's t-distribution

The Student's t-distribution arises when estimating the mean of a normally distributed population in situations where sample size is small and population variance is unknown. Its pdf is:

where is the degrees of freedom.

- Support:

- Parameter: degrees of freedom

- Mean & variance: The mean is 0 for . The variance is for . For lower , these moments may be undefined.

- Heavier tails: More prone to outliers than the normal. As , it converges to the normal distribution.

- Use cases: In regression models, the t-distribution is favored in small-sample scenarios or when outliers are present.

F-distribution

An F-distribution is the distribution of a ratio of two chi-square variables, each divided by their respective degrees of freedom. Specifically, if and , then:

follows an F-distribution with degrees of freedom.

- Support:

- Parameters: (degrees of freedom)

- Use cases: Widely used in ANOVA, comparing variances in different populations, or model comparison in regression.

- Parameter estimation: Typically arises in test statistics. Direct "fitting" is less common in routine ML pipelines, but occasionally used in specialized modeling.

Weibull distribution

A Weibull distribution has the pdf:

- Support:

- Parameters: shape , scale

- Use cases: Time-to-failure or survival analysis, reliability engineering, wind speed distributions.

- Special cases: If , it becomes the exponential distribution.

- Parameter estimation: Methods include MLE and method of moments. Often used in engineering to estimate lifetimes of components.

Log-normal distribution

A random variable is log-normally distributed if is normally distributed. The pdf is:

- Support:

- Parameters: are the mean and standard deviation of the log-transformed variable

- Use cases: Modeling skewed positive data (e.g., certain economic or biological variables).

- Parameter estimation: Typically done by fitting a normal distribution to the log of the data. MLE is straightforward: estimate the mean and variance of .

Special distributions in machine learning

Pareto distribution

The Pareto distribution is a heavy-tailed distribution often used in scenarios exhibiting power-law characteristics, such as wealth distribution or file size distributions on the internet. Its pdf is:

- Support:

- Parameters: scale , shape

- Heavy tails: As grows, the distribution decays slowly compared to exponential or Gaussian, making large outliers more probable.

- Use cases: Modeling phenomena with "the rich get richer" dynamics or extreme outliers. In ML, can inform heavy-tailed priors or anomaly detection in big data.

- Parameter estimation: MLE is . Because of the heavy tail, robust estimation techniques are sometimes used to mitigate the impact of outliers.

Laplace distribution

Also called the double exponential distribution, the Laplace distribution has pdf:

- Parameters: location , diversity

- Use cases: In machine learning, the Laplace distribution is central in L1 regularization (Lasso). It has heavier tails compared to the normal distribution, yielding robust behavior against outliers.

- Parameter estimation: The MLE for is the median of the data (rather than the mean), and is the average absolute deviation from the median.

Gumbel distribution

A Gumbel distribution is often used in extreme value theory for modeling maxima of samples. One form of the pdf is:

- Parameters: location , scale

- Use cases: Modeling extreme events, such as maximum rainfall in a year or worst-case loads on servers. Also arises in logistic regression link functions (the "logit" can be related to a Gumbel distribution difference).

- Parameter estimation: MLE or method of moments are standard. In practice, specialized libraries implement these fittings.

Cauchy distribution

A Cauchy distribution has the pdf:

- Parameters: location , scale

- Undefined mean & variance: Unlike most common distributions, the Cauchy has undefined (infinite) mean and variance. This makes parameter estimation challenging.

- Heavily heavy-tailed: Rare but extremely large values occur with non-negligible probability.

- Use cases: Often a cautionary example of distributions that defy certain classical statistical intuitions. Rarely used in direct modeling but important conceptually.

Dirichlet distribution

The Dirichlet distribution generalizes the Beta distribution to higher dimensions, producing a probability vector in a -simplex. Its pdf, for and , is:

where is now the multinomial beta function, and are the parameters.

- Support: The -dimensional simplex

- Use cases: Bayesian modeling of categorical or multinomial parameters, topic modeling (LDA uses Dirichlet priors), mixture models, and any problem requiring a distribution over distributions.

- Parameter estimation: Typically done in a Bayesian context. If data are in the form of multiple categorical draws, the posterior distribution of probabilities is also Dirichlet when using a Dirichlet prior.

Conclusion

Choosing the right distribution is crucial for accurate modeling and inference. Discrete distributions like Bernoulli, Binomial, and Poisson help in scenarios with count data or binary outcomes, while continuous ones like Gaussian, Exponential, and Gamma cater to a wide range of phenomena — time-to-event analyses, large-sample approximations, or uncertain probability estimates. Heavy-tailed or specialized distributions (Pareto, Laplace, Cauchy, Gumbel, Dirichlet) are invaluable in certain extreme or specialized ML contexts.

It's important to:

- Check assumptions (e.g., independence, identical distribution, shape properties).

- Estimate parameters reliably using MLE, method of moments, or Bayesian methods.

- Understand relationships (e.g., exponential is a special Gamma, Beta is a prior for Bernoulli/binomial, etc.).

In practice, data scientists should explore multiple distributions, compare goodness-of-fit, and always remember to validate model assumptions with domain knowledge and empirical tests.

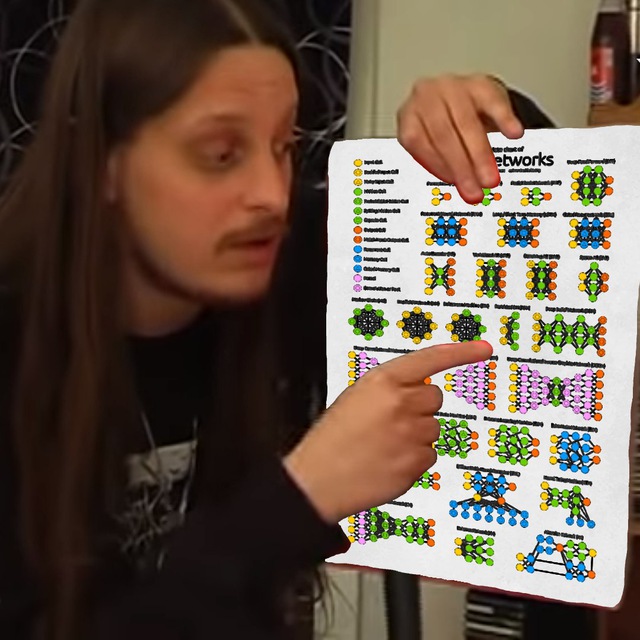

An image was requested, but the frog was found.

Alt: "Distribution selection"

Caption: "Selecting an appropriate distribution depends on the nature of the data, assumptions, and analysis goals."

Error type: missing path

Below is a brief Python snippet illustrating how to sample from and plot some of these distributions using SciPy is a Python library providing many numerical routines including probability distributions.:

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from scipy.stats import bernoulli, binom, norm, gamma

# Example: generate random data and plot histograms for different distributions

np.random.seed(42)

bern_data = bernoulli.rvs(p=0.3, size=1000)

binom_data = binom.rvs(n=10, p=0.3, size=1000)

norm_data = norm.rvs(loc=0, scale=1, size=1000)

gamma_data = gamma.rvs(a=2, scale=1/0.5, size=1000) # shape=2, rate=0.5

fig, axes = plt.subplots(2, 2, figsize=(8, 6))

axes[0,0].hist(bern_data, bins=[-0.5, 0.5, 1.5], density=True, alpha=0.7, color='blue')

axes[0,0].set_title("Bernoulli(p=0.3)")

axes[0,1].hist(binom_data, bins=np.arange(12)-0.5, density=True, alpha=0.7, color='green')

axes[0,1].set_title("Binomial(n=10, p=0.3)")

axes[1,0].hist(norm_data, bins=30, density=True, alpha=0.7, color='red')

axes[1,0].set_title("Normal(0,1)")

axes[1,1].hist(gamma_data, bins=30, density=True, alpha=0.7, color='purple')

axes[1,1].set_title("Gamma(k=2, rate=0.5)")

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Through real-world applications and further chapters in this course, you'll see how choosing appropriate distributions impacts inference, hypothesis testing, and the performance of machine learning models.