🎓 85/2

This post is a part of the Transformers educational series from my free course. Please keep in mind that the correct sequence of posts is outlined on the course page, while it can be arbitrary in Research.

I'm also happy to announce that I've started working on standalone paid courses, so you could support my work and get cheap educational material. These courses will be of completely different quality, with more theoretical depth and niche focus, and will feature challenging projects, quizzes, exercises, video lectures and supplementary stuff. Stay tuned!

Sentence transformers refer to transformer-based architectures specifically optimized for generating dense vector representations of entire sentences, rather than isolated words or subwords. Unlike traditional word embedding techniques that capture meaning at the token level, sentence transformers compute an embedding that encapsulates the broader context and semantics of a complete sentence. The goal is to produce a numerical vector — usually of fixed dimensionality — that can be used to compare the similarity of two sentences or to perform tasks such as clustering sentences by meaning.

The concept of obtaining a single embedding per sentence became particularly popular through approaches like Sentence-BERT (Reimers and Gurevych, 2019). This approach extends the classic BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) architecture with specialized training objectives that encourage semantically similar sentences to be close in the embedding space. The reason for focusing on entire sentences, rather than individual words, is that many natural language processing (NLP) tasks — for instance, paraphrase detection or semantic search — require an understanding of an entire phrase or sentence.

When I discuss a "dense vector representation" of a sentence, I mean that each sentence is mapped to a vector in (for some dimension ) such that semantically related sentences reside close to each other by a chosen distance metric like Euclidean distance or by measuring angular similarity (e.g., cosine similarity). Thus, if two sentences convey the same meaning, their embeddings end up almost adjacent in this space; if their meanings differ substantially, their embeddings will be more distant.

key advantages

One of the central advantages of sentence transformers is their ability to encode contextual meaning at the sentence level. Although popular word embeddings (e.g., Word2Vec or GloVe) produce embeddings that capture some aspects of a token's usage, they typically rely on local context windows and cannot encode the full nuance of a complete sentence. Traditional word embeddings also do not dynamically shift depending on the entire sentence's semantics — a shortcoming addressed by contextual embeddings such as BERT or RoBERTa.

However, even with contextual embeddings from general-purpose language models, one obtains a sequence of token embeddings rather than a single representation for the entire sentence. A sentence transformer bridges this gap by introducing specific pooling layers or carefully designed architectures to produce a single, fixed-length vector from the entire token sequence. This extra step is highly beneficial for tasks where we need a direct numeric measure of sentence-to-sentence similarity, or for downstream tasks such as ranking, clustering, or retrieval.

Compared to naive pooling of token embeddings in a general-purpose transformer, sentence transformers are explicitly trained with objectives that align sentences with similar meanings more closely. This yields robust sentence-level representations that consistently outperform raw, untrained pooling strategies.

importance in nlp

Sentence transformers have revolutionized many standard NLP tasks. For instance, semantic search — a core functionality in modern knowledge-based systems — relies heavily on quickly evaluating the similarity between user queries and potential relevant documents or passages. Here, having a single embedding for each query and each candidate text snippet dramatically reduces computation. One can compare embeddings via a simple vector similarity measure, rather than performing complicated, token-by-token alignments each time.

Beyond semantic search, sentence embeddings are critical in paraphrase detection (determining if two sentences essentially convey the same idea), clustering (grouping sentences by topic), and summarization tasks. They also facilitate advanced tasks like zero-shot classification, where a sentence embedding can be compared to label embeddings, or combined with specialized textual prompts for tasks that do not have explicit training data.

Researchers and practitioners alike often reference sentence transformers as a state-of-the-art approach for capturing the deeper semantics of text. As language models continue to evolve — from BERT to RoBERTa, to XLM-R for multilingual embeddings, and beyond — the sentence transformer paradigm remains an indispensable technique for many real-world NLP systems.

underlying transformer architecture

transformer model refresher

Sentence transformers build on the foundational transformer architecture introduced by Vaswani and gang (2017), which revolutionized NLP with its attention-based mechanism. The original transformer is composed of encoder and decoder blocks. In the context of sentence encoders like BERT, we typically only use the encoder stack to process the input text. This encoder includes:

- Multi-head self-attention layers: These layers compute attention weights over every pair of input tokens, capturing global contextual dependencies.

- Feed-forward layers: Position-wise feed-forward networks that expand and project the embeddings, contributing to model capacity.

- Positional encoding or learned positional embeddings: Since the transformer does not use recurrence, it relies on position embeddings to retain sequential information.

When we say that BERT is a bidirectional encoder, we mean that the self-attention mechanism can attend to all tokens on both sides (left and right) of a target position, thereby capturing deep contextual dependencies. A sentence transformer typically reuses one or more of these pre-trained transformer encoder blocks as its backbone but extends or modifies them to output a single sentence-level embedding.

pooling strategies

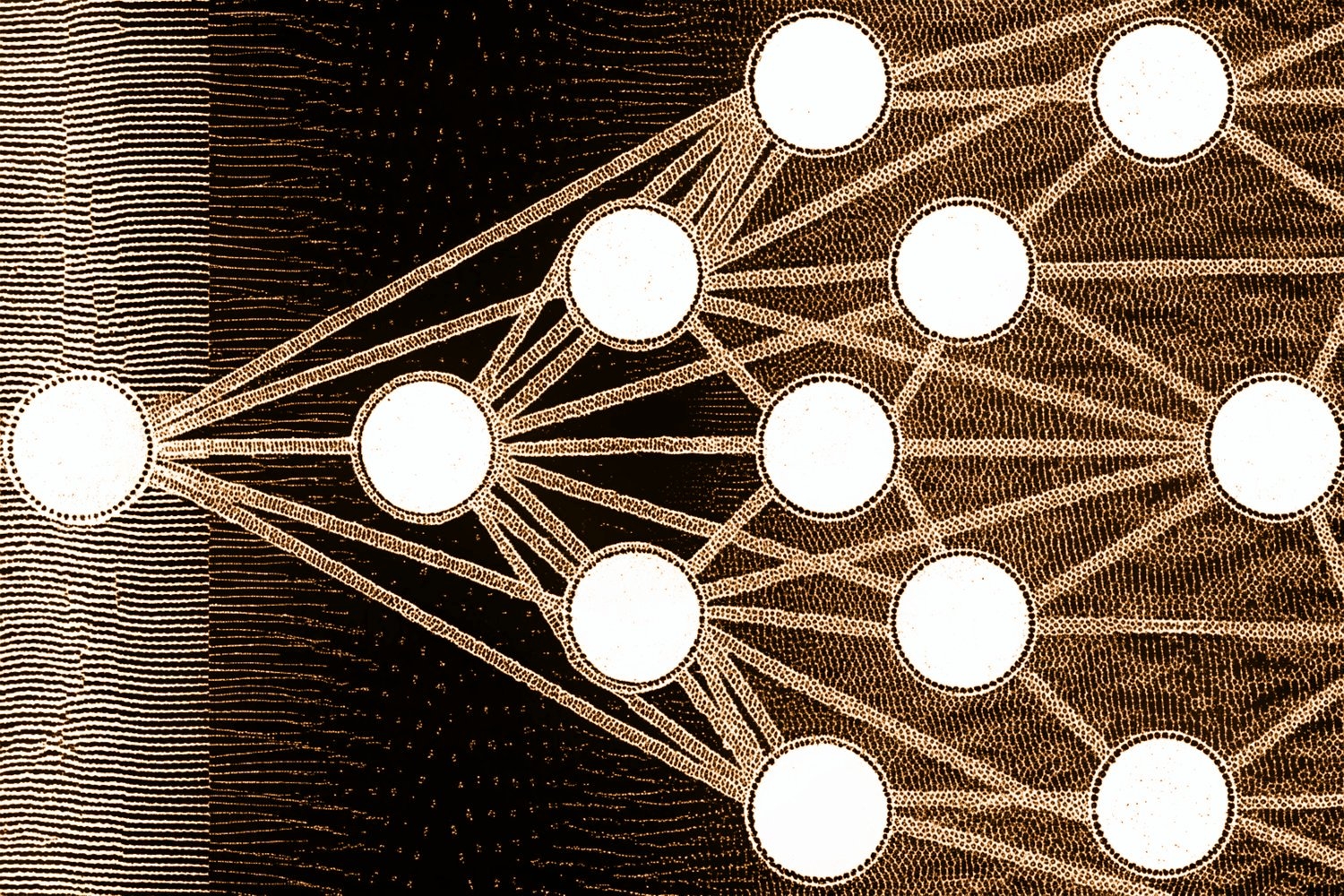

Central to sentence transformers is the step of condensing a token-level output from the transformer encoder into one vector. Common pooling strategies include:

- [CLS] token pooling: Many BERT-based architectures prepend a special classification token ([CLS]) to every sentence. The hidden state at this special token is occasionally used as the entire sequence embedding. However, for tasks like semantic similarity, this approach can be suboptimal unless specifically fine-tuned.

- Mean pooling: Another popular approach is to take the element-wise mean of all token embeddings in the final transformer layer (excluding special tokens). This average representation often yields strong performance for semantic tasks, particularly when the model has been trained with a contrastive or triplet objective tailored to sentence-level similarity.

- Max pooling: A less common but sometimes effective approach is to take the maximum over each embedding dimension across the token embeddings. This can help highlight the most dominant features across tokens.

Empirical work (e.g., Reimers and Gurevych, 2019) has shown that mean pooling is often more stable for semantic similarity tasks, leading to better results than simply taking the [CLS] token state.

siamese and triplet networks

A crucial design for sentence transformers involves constructing a Siamese network architecture. The name "Siamese" refers to using two (or more) identical subnetworks that share weights, meaning they have the same parameters. Typically, each subnetwork is a transformer encoder producing a sentence embedding. If we label these subnetworks (parametrized by ), then for two sentences and , we generate embeddings:

These embeddings and are then compared using a distance or similarity function (e.g., cosine similarity, Euclidean distance) depending on the training objective. For instance, if the objective is to minimize the distance between paraphrase pairs, we might use a contrastive loss that pulls paraphrased sentences closer while pushing non-paraphrased pairs apart.

In a triplet network, we extend this idea to three sentences at a time: , , and . We want:

- The distance between and to be small (because they should be semantically similar).

- The distance between and to be large.

This yields the well-known triplet loss:

where is a distance function (cosine or Euclidean), and is a margin that ensures a minimum separation between positive and negative pairs. The embeddings are derived from the same transformer . This approach fosters the creation of an embedding space where semantic relationships are more accurately reflected in distances.

differences from traditional word embeddings

contextual understanding

The hallmark of sentence transformers is their ability to incorporate context from the entire sentence into each vector. Traditional word embedding approaches, such as Word2Vec or GloVe, capture an individual token's representation based on local co-occurrence statistics across a corpus. They cannot, however, re-interpret a word differently depending on the other tokens present in the sentence. Even context-based embeddings like ELMo or BERT produce embeddings for each token (or subword) but do not directly yield a single embedding capturing the entire sentence meaning.

By design, sentence transformers produce a single embedding that factors in the interplay among all tokens. This global perspective is crucial for tasks like semantic similarity, because the combined meaning of a sentence may not be trivial to deduce by looking at tokens individually. For instance, "I appreciate advanced mathematics as a discipline" differs from "I find advanced mathematics challenging to understand," even if the keywords (like "advanced," "mathematics") overlap. Sentence-level embeddings can capture such distinctions by focusing on the entire context.

dimensionality and embedding space

Word embeddings are typically in a range of 50–300 dimensions (in older approaches) or up to 768–1024 dimensions for each token in BERT-based models. Sentence transformers often produce embeddings in the same dimensional range as the underlying transformer's hidden size. For instance, a base BERT model might have a hidden state size of 768, so naive pooling could yield 768-dimensional sentence vectors. Researchers and developers sometimes reduce these embeddings to a lower dimension (e.g., 256 or 384) if that helps with computational efficiency or downstream performance, commonly by applying a projection layer on top of the pooled output.

In the embedding space of a well-trained sentence transformer, semantically similar sentences cluster together. These clusters can cross topical or domain boundaries; for example, an embedded representation of "How do I bake a chocolate cake?" is likely to be near "What's the best way to make brownies?" if the model's domain knowledge about cooking is robust.

semantic alignment

A crucial difference between sentence transformers and traditional word embeddings is that the former can directly align entire sentences. This means that if we perform a cosine similarity between two sentence embeddings, that measure strongly correlates with human judgments of sentence-level similarity or relatedness. In contrast, with word embeddings, one might try to average or sum the token vectors, but the result is typically suboptimal without specialized training. By specifically optimizing sentence transformers to discriminate or relate entire sentences, we achieve far superior performance in tasks requiring textual entailment, paraphrasing, or semantic alignment.

Furthermore, the alignment properties of sentence transformers extend across paraphrases, synonyms, and near-synonyms. A robust sentence embedding model can even discover that "I want to discover new methods in mathematics" is quite close to "I'm looking to explore novel techniques in math." This level of semantic alignment is what drives their popularity for multiple real-world applications.

training objectives and datasets

contrastive learning

Many sentence transformer training regimes rely on contrastive learning, a technique where the model sees pairs (or triplets) of sentences labeled as semantically similar or dissimilar. The model then updates weights so that embeddings for similar sentences are brought closer together, while embeddings for dissimilar pairs are pushed apart. A basic contrastive loss function might look like:

Here, and are sentence embeddings, is a distance metric, indicates whether the pair is similar () or dissimilar (), and is a margin to enforce a minimum separation between negative pairs. The details of the loss function can vary, but the principle remains: the model learns to differentiate sentences based on real similarity labels.

An example of labeled data for contrastive learning might be drawn from a paraphrase corpus like the Microsoft Research Paraphrase Corpus (MRPC) or the Quora Question Pairs dataset, where each pair is marked as duplicate or not. Another popular resource is the SNLI (Stanford Natural Language Inference) dataset, which labels sentence pairs as entailing, contradicting, or neutral.

supervised training data

While contrastive learning can be considered partly supervised (we have labels for similarity), there are also more explicit supervision approaches. These might involve regression-based training (e.g., training the model to output a similarity score matching a human-provided label) or classification-based training (e.g., labeling pairs as paraphrases vs. not paraphrases).

A prime example is Sentence-BERT, which uses pairs of sentences from the SNLI and MultiNLI corpora. The model sees sentence pairs labeled as "entailment", "contradiction", or "neutral." From these labels, it constructs a classification or regression objective that correlates strongly with semantic similarity. The model parameters adjust accordingly, improving the representation's ability to capture the subtle differences among entailed (very similar) or contradictory (very dissimilar) sentences.

unsupervised methods

Not all tasks have extensive labeled data available. Hence, unsupervised or self-supervised methods can also be leveraged for training sentence transformers. One approach is to take advantage of massive unlabeled text corpora and create pseudo-pairs. For instance, consecutive sentences or augmented versions of a single sentence might be considered semantically close, while randomly chosen sentences from different documents might be considered dissimilar.

Some advanced techniques also use data augmentation: rewriting or partially masking a sentence, or generating random transformations (e.g., synonyms substitution). The anchor and augmented sentences form a positive pair. Over large corpora, a model can learn robust sentence representations even without a direct human-labeled dataset. However, purely unsupervised training typically requires large-scale data and substantial computational resources to reach the quality levels of supervised or semi-supervised approaches.

key applications

semantic search

One of the earliest and most influential uses of sentence transformers lies in semantic search. By embedding both queries and candidate documents (or passages, or sentences) into a common vector space, we can easily retrieve the top-k most relevant candidates by computing their vector similarities. For instance, a user might ask, "What is the capital of France?" and the system, upon embedding the user's question, compares it to the embeddings of sentence-level text in a knowledge base. The candidates with the highest cosine similarity (or the smallest Euclidean distance) are returned as potential answers or relevant passages.

This approach dramatically reduces the computational overhead compared to naive textual similarity computations that might rely on token-level matching or more complicated alignment. Instead, each piece of text is converted once to a vector, and subsequent queries are also vectorized. The retrieval step thus becomes a matter of comparing two vectors, which is extremely fast, especially if advanced similarity search structures (e.g., approximate nearest neighbor search) are used.

paraphrase detection

Paraphrase detection measures whether two sentences effectively communicate the same concept. For instance, the pair "I enjoy reading advanced materials" and "I like going through sophisticated texts" are close paraphrases, even if they share few words in common. Sentence transformers trained on paraphrase identification tasks (like those from the Quora Question Pairs or MRPC datasets) are adept at picking up subtle differences or equivalences in meaning.

Once the model is trained, paraphrase detection becomes straightforward: embed both sentences, then compute the cosine similarity. If it exceeds a threshold, the system concludes they are paraphrases. This technique is widely used in tasks like deduplicating user-generated content, detecting repeated questions in a forum, or identifying near-duplicate text in large corpora.

clustering and topic modeling

Beyond direct pairwise similarity, the embeddings from sentence transformers lend themselves to clustering. Suppose we have a collection of documents or sentences. By converting them all to embeddings, we can group them using clustering algorithms (like k-means or hierarchical clustering) to discover underlying themes or topics. Because the sentence embeddings reflect semantic similarity, the clusters typically correspond to meaningful topics or subtopics, even if the sentences do not share the same keywords.

Topic modeling, traditionally performed by methods like LDA (Latent Dirichlet Allocation), can also be complemented or replaced by embedding-based clustering. In some scenarios, a combination of clustering plus dimensionality reduction (e.g., UMAP or t-SNE) on top of sentence embeddings is used to visualize textual datasets, revealing interesting groupings or anomalies.

question answering and dialogue systems

The capacity of sentence transformers to encode broad contextual meaning significantly improves the quality of question answering (QA) and dialogue systems. For open-domain QA, a typical pipeline might embed the user's question, embed all candidate passages from a large text corpus, and then select the top passages with the highest similarity as potential sources of the answer. A more advanced system can subsequently re-rank these passages or generate an answer from them.

In dialogue systems and chatbots, sentence embeddings help identify user intent, find relevant knowledge base entries, or identify the best response candidate in a multi-turn conversation. As conversation flows, each utterance can be transformed into an embedding. The system can then track the semantic context and retrieve or generate responses that maintain coherence and continuity.

implementation and tools

popular libraries

- Sentence-BERT (SBERT): One of the most widely used repositories for sentence transformers is the official Sentence-BERT repository (from Reimers and Gurevych). It provides a straightforward Python API for fine-tuning and inference, built on top of the Hugging Face Transformers library.

- Hugging Face Transformers: The Hugging Face ecosystem offers a robust platform for transformer models. While it does not specifically implement sentence transformers in the core library (it primarily supplies pretrained models for token-level tasks), many community-driven or official expansions exist that adapt these models for sentence embedding purposes.

An example usage with the sentence-transformers library in Python might look like:

from sentence_transformers import SentenceTransformer

# Download a pre-trained SBERT model:

model = SentenceTransformer('all-MiniLM-L6-v2')

sentences = [

"I really love advanced machine learning concepts",

"I'm a big fan of theoretical computer science",

"This sentence is unrelated"

]

# Compute embeddings

embeddings = model.encode(sentences)

# Compare similarities

import numpy as np

similarity_01 = np.dot(embeddings[0], embeddings[1]) / (np.linalg.norm(embeddings[0]) * np.linalg.norm(embeddings[1]))

similarity_02 = np.dot(embeddings[0], embeddings[2]) / (np.linalg.norm(embeddings[0]) * np.linalg.norm(embeddings[2]))

print("Similarity between sentence 0 and 1:", similarity_01)

print("Similarity between sentence 0 and 2:", similarity_02)

In this short snippet, we load a popular pretrained model called "all-MiniLM-L6-v2". Then we encode some sample sentences into embeddings, and finally compute pairwise cosine similarities. Notice that the first two sentences might yield a higher similarity due to shared conceptual fields (machine learning, theoretical aspects, etc.), whereas the third sentence is presumably unrelated, thus the similarity is lower.

model selection

Selecting the underlying transformer architecture can significantly affect performance, speed, and resource requirements. For example:

- BERT-base (12 layers, 768 hidden size): A good baseline for many tasks.

- RoBERTa: Typically yields better performance on certain benchmarks due to optimized pretraining.

- DistilBERT: A smaller and faster model with fewer parameters, good for resource-constrained environments or real-time inference.

- MiniLM: Another lightweight approach that is quite performant for sentence embeddings.

- XLM-R: Useful for multilingual tasks, if cross-lingual or multi-lingual sentence embeddings are needed.

When deciding on a model, I have to consider domain mismatch. If the text differs significantly from standard corpora (e.g., legal, clinical, or technical domains), domain-adaptive pretraining or fine-tuning might be necessary. This typically involves continued pretraining on domain-specific data to produce better domain-aligned embeddings.

deployment considerations

Real-world deployment of sentence transformers involves balancing inference speed, memory usage, and accuracy. Sentence transformer models, especially those based on large BERT-like backbones, can be relatively heavy. Some important considerations:

- Inference hardware: GPU-accelerated inference is typically much faster than CPU-based inference, but GPU resources might be costly or limited.

- Batching: Batching sentences together significantly boosts throughput, but one must manage latency constraints.

- Quantization or knowledge distillation: Techniques such as 8-bit or 16-bit quantization can reduce memory usage. Distillation can lead to smaller, faster student models.

- Approximate nearest neighbor (ANN) search: For semantic search or large-scale retrieval, storing embeddings in a specialized ANN index (e.g., FAISS, Annoy, or HNSW libraries) can facilitate sub-millisecond similarity queries across millions or billions of embeddings.

Once a model is set up, modern MLOps pipelines might incorporate the process of continuously monitoring performance, retraining as new data arrives, and automatically deploying updated models. For large-scale systems, it's often beneficial to keep embeddings precomputed in a vector database (like Pinecone, Milvus, or other specialized vector stores), so that retrieval can be performed in real time.

evaluation and performance metrics

similarity measures

The embeddings produced by sentence transformers are typically compared using:

-

Cosine similarity: Evaluates the cosine of the angle between two vectors and . It is scale-invariant, making it a popular choice in text processing. Cosine similarity is given by:

-

Euclidean distance: In some settings, measuring the distance between embeddings is more intuitive. However, it can be influenced by vector magnitude.

-

Dot product: Another approach is to directly compute the dot product . Models that produce normalized vectors or rely on scale control (e.g., a temperature parameter) might favor dot product measures.

In practice, if I want to measure how "close" two sentences are, I usually pick one measure consistently. Cosine similarity remains the most common default in the sentence embedding literature.

benchmark datasets

Empirically evaluating sentence transformers often involves using established benchmark datasets, such as:

- STS (Semantic Textual Similarity) tasks: Datasets like STS-B (Semantic Textual Similarity Benchmark) provide pairs of sentences with human-annotated similarity scores (on a scale of 0 to 5). The Spearman correlation between predicted similarity (e.g., from cosine similarity of embeddings) and these human judgments is a standard measure of model quality.

- GLUE: The General Language Understanding Evaluation benchmark comprises multiple tasks, including textual entailment and similarity tasks. Sentence embedding models can be tested on relevant subsets of GLUE (like MRPC, STS-B, etc.).

- Quora Question Pairs: A dataset of question pairs labeled as duplicate or not.

- Microsoft Research Paraphrase Corpus (MRPC): This set of sentence pairs from news sources is labeled as paraphrase or not paraphrase.

Performance improvements of a fraction of a correlation point can indicate meaningful progress, especially for well-tuned models. Additionally, domain-specific evaluations (e.g., biomedical STS tasks) might be used if the model is specialized for a certain domain.

error analysis

Effective development of sentence transformers also involves analyzing cases where the model fails. Sometimes the embedding might reflect spurious correlations or be easily confused by complex negations, domain-specific jargon, or sarcasm. Domain shift can also degrade performance. For example, a model trained on general English might struggle with social media text or specialized legal language.

Performing error analysis often involves:

- Examining pairs of sentences that the model assigns high similarity but are in fact dissimilar (false positives).

- Studying pairs that are semantically close but which the model deems far apart (false negatives).

- Considering ambiguous sentences with multiple interpretations.

- Looking at examples that break the assumption of standard grammar or typical language use (like code-mixed text or text full of slang).

By identifying systematic errors, we can decide whether additional fine-tuning data or domain adaptation techniques are needed.

advancements and future directions

multilingual embeddings

A rapidly evolving subfield of sentence transformer research centers on multilingual or cross-lingual embeddings. For example, XLM-R-based models can produce embeddings for sentences in multiple languages such that semantically equivalent sentences from different languages remain close in the common vector space. This is invaluable for cross-lingual search (a query in one language retrieving documents in another) or multilingual paraphrase detection.

Research in cross-lingual sentence transformers often focuses on bridging distribution gaps between languages with different writing systems, morphological complexities, or syntactic structures. Various forms of domain adaptation or knowledge distillation can produce multilingual models that approach the quality of single-language sentence embeddings.

domain adaptation

Domain adaptation is crucial when the training data (often general English corpora) diverges from the domain of interest (e.g., legal contracts, scientific articles, or social media). Domain adaptation for sentence transformers commonly proceeds through:

- Further pretraining on an unlabeled domain-specific corpus using masked language modeling.

- Supervised fine-tuning on labeled data from the domain if it is available (e.g., annotated paraphrases from the domain or domain-specific STS tasks).

- Mining domain paraphrases (semi-supervised) by heuristics or distant supervision, then using them in contrastive learning.

research outlook

As sentence transformers mature, new directions continue to emerge:

- Handling very long documents: Standard transformer models have input length limits (often 512 tokens). Some approaches combine hierarchical transformers or chunking strategies to represent entire paragraphs or documents, then pool them together.

- Zero-shot and few-shot learning: By leveraging large-scale language models, more advanced techniques can produce robust sentence embeddings even with minimal task-specific data.

- Enhanced negative sampling: Current contrastive or triplet-based methods can struggle when negative examples are not semantically tricky enough. Future approaches might incorporate advanced negative sampling, making the model more discriminative.

- Efficiency and compression: Ongoing efforts to reduce the computational footprint include quantization, low-rank factorization, and knowledge distillation, ensuring that sentence transformers can run efficiently on edge devices or within stringent latency constraints.

In summary, sentence transformers are a linchpin in modern NLP systems, powering everything from semantic search to paraphrase detection, and from topic clustering to advanced dialogue systems. By leveraging the underlying power of the transformer encoder architecture and specialized training objectives tailored to sentence-level semantics, these models deliver strong performance across a variety of real-world tasks. Their development continues at a rapid pace, with researchers extending them to handle multilingual settings, specialized domains, and ever longer or more complex inputs.

An image was requested, but the frog was found.

Alt: "Conceptual diagram of a Siamese Sentence Transformer"

Caption: "A simplified schematic shows two identical Transformer encoders (sharing weights) taking in two different sentences and producing embeddings that can be compared for semantic similarity."

Error type: missing path

If I had to highlight one practical takeaway, it is that sentence embeddings enable us to harness pre-trained language model power not just at the token level, but at the sentence (and potentially paragraph or document) level. This synergy of advanced neural architectures and well-designed objectives paves the way for more accurate and context-aware textual analysis, making sentence transformers a core component of contemporary NLP pipelines.