🎓 117/2

This post is a part of the Specialized & advanced architectures educational series from my free course. Please keep in mind that the correct sequence of posts is outlined on the course page, while it can be arbitrary in Research.

I'm also happy to announce that I've started working on standalone paid courses, so you could support my work and get cheap educational material. These courses will be of completely different quality, with more theoretical depth and niche focus, and will feature challenging projects, quizzes, exercises, video lectures and supplementary stuff. Stay tuned!

The idea of generating images pixel-by-pixel may seem both intuitive and daunting in equal measure. On the one hand, images are naturally composed of discrete pixels — each of which can, in principle, be drawn from some distribution — but on the other hand, the dependencies between pixels can be vastly complex and high-dimensional. Many approaches in generative modeling have tackled this problem through implicit probability models (such as Generative Adversarial Networks) or latent-variable models (such as Variational Autoencoders), which sidestep a direct, explicit modeling of each pixel's probability in favor of more abstract representations. However, PixelRNN and PixelCNN are noteworthy in that they remain firmly rooted in the autoregressive paradigm. They explicitly factor the joint distribution of an image over its pixels via the chain rule of probability and attempt to capture as much local and global context as possible to produce realistic samples.

The key insight behind these models is that each pixel in an image can be modeled as conditioned on all previously generated pixels . In other words, one can apply a factorization:

where represents the image of size (for simplicity, grayscale or a single channel; for color images, each pixel intensity can be broken down into color channels). Models based on this approach had been studied in earlier works, but the introduction of PixelRNN and PixelCNN in 2016 (van den Oord and gang, NeurIPS 2016) was a watershed moment, showcasing that purely autoregressive generative models could produce high-quality images, even though at the time they could not rival the best Generative Adversarial Networks in terms of photorealism.

In this article, I dive deeply into the fundamentals of pixel-based generative modeling and the specific architectural choices behind PixelRNN and PixelCNN. I will also compare the two approaches in terms of performance, scalability, and image quality, explore some of their variants (including Gated PixelCNN or PixelCNN++), discuss how one might implement them in practice, and finally look at some of their most common applications and real-world use cases. Along the way, I will incorporate references to the relevant research and expansions on the theoretical underpinnings, so that you come away with a solid grasp of how these models work and why they remain important in modern generative modeling.

An image was requested, but the frog was found.

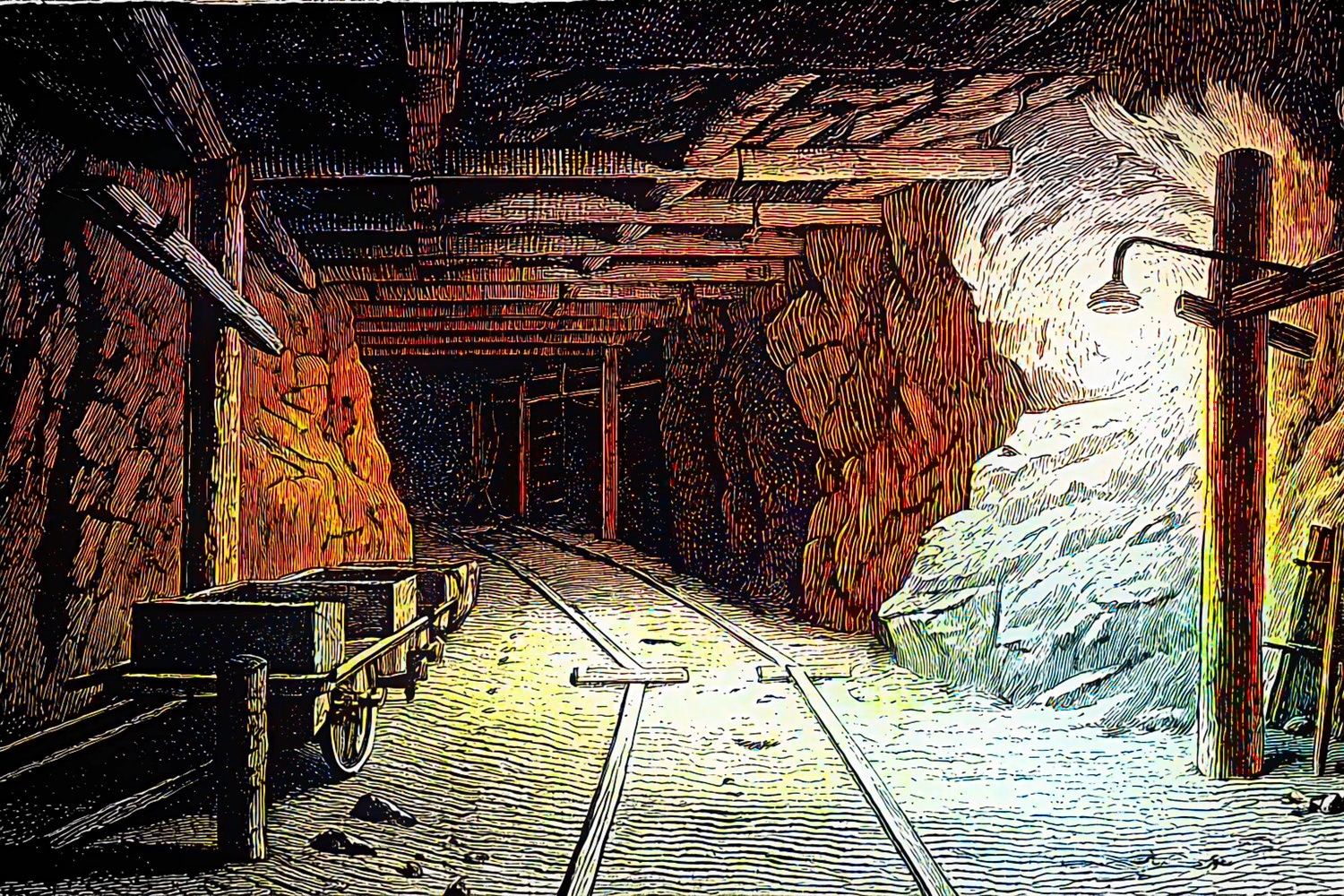

Alt: "An example usage of PixelRNN/PixelCNN"

Caption: "Illustration of pixel-level generation concepts in action. Each pixel is predicted conditioned on previously generated pixels."

Error type: missing path

Fundamentals of pixel-based generative modeling

Conditional probability distributions, factorization of the joint distribution, importance of receptive fields

At the heart of pixel-based generative modeling is the factorization of an image's joint distribution. For an image of size (we will generalize later to color images or rectangular images), we can flatten it into a vector of length in a raster-scan order:

where corresponds to the top-left pixel, the next pixel in the row, and so forth, row by row. The fundamental assumption is that each pixel depends on all the previous ones in this flattened sequence, so:

This direct factorization is perfectly valid from a theoretical standpoint; however, implementing it naively poses enormous computational and modeling challenges. An autoregressive neural network can be designed to approximate , but how does one effectively capture the context of potentially thousands of previously seen pixels?

The solution is to carefully structure the receptive field in a network so that each pixel's prediction only depends on the relevant subset of previously generated pixels. In an image, the most crucial immediate context is usually found in nearby pixels — including those above it, to the left, and sometimes in diagonally adjacent locations. In an RNN-based approach (PixelRNN), recurrent connections enforce dependencies from previously processed positions. In a CNN-based approach (PixelCNN), carefully masked convolutions are used to prevent "seeing" future pixels. The key concept, in either approach, is to ensure that each pixel can incorporate the relevant dependencies while respecting the autoregressive ordering.

Why is this ordering constraint so important? Because if a pixel can inadvertently "see" the value of a future pixel during training, the model will cheat. It would inadvertently glean information about what it is supposed to predict, destroying the validity of the factorization. Masked convolutions are, therefore, a crucial design choice: they block the flow of information from future or rightward / downward positions in the image, preserving the correct autoregressive conditioning.

In summary:

- We are predicting each pixel by conditioning on a subset of previously generated pixels.

- The choice of architecture heavily influences how these dependencies are captured (e.g., LSTMs scanning the image or convolutional networks with carefully placed masks).

- Ensuring the model only has access to truly "past" pixels is crucial for correct and stable training.

Next, let's explore the specifics of PixelRNN, which was originally introduced to handle these dependencies with recurrent neural network modules.

PixelRNN

Core architecture

PixelRNN is built on the fundamental principle that an RNN can be unrolled pixel-by-pixel (or row-by-row, or diagonal-by-diagonal) to model the conditional distributions . This approach is reminiscent of earlier attempts to use 2D recurrent structures for image modeling (for instance, works on Spatial LSTMs). However, the direct 2D RNN approach can be extremely slow, because for each pixel, one needs the hidden state from all relevant neighboring positions.

To mitigate this, the PixelRNN authors introduced specialized LSTM variants, notably RowLSTM and Diagonal BiLSTM, each providing different trade-offs between computation speed and the quality of captured dependencies.

The overall PixelRNN architecture (van den Oord and gang, 2016) can be summarized as follows:

- Masked convolution (MaskA) to handle the earliest layers of processing (ensuring that each pixel only receives information from previously seen pixels and channels).

- Several RNN layers in one of two configurations:

- RowLSTM or

- Diagonal BiLSTM

- Additional convolutional or residual layers (with possible dimension-reduction blocks).

- A final convolution that produces logits for a Softmax distribution over possible pixel intensities (for each color channel, if in color).

The masked convolution portion ensures that no future pixels are visible when we pass the input to the recurrent layers. The recurrent layers handle the context. Finally, the softmax or logistic mixture output layer predicts the distribution of each pixel intensity.

An image was requested, but the frog was found.

Alt: "Visualization of PixelRNN/PixelCNN approach"

Caption: "Example depiction of how each pixel depends on previously processed pixels."

Error type: missing path

Masked convolutions and dependencies

The "masked convolution" concept is shared by PixelRNN and PixelCNN. Here, the convolution kernel is intentionally "blocked" or set to zero for weights that correspond to future or rightward positions relative to the current pixel. By convention, two types of masks are often discussed in the PixelCNN/PixelRNN literature:

- MaskA: used to ensure that the current pixel does not have access to itself or subsequent channels within a color pixel (in color images). For example, if you're generating the red channel of pixel (i,j), you shouldn't see the green or blue channels for that same pixel.

- MaskB: used at later layers, allowing the model to see the current channel of previously generated color channels, while still preventing it from peeking at future pixel positions.

In PixelRNN, these masks appear in the earliest convolutional layers (the "input-to-state" transformations). Once the data is passed into the LSTM or RNN blocks, the recurrence ensures that only "past" pixel information is propagated. The combination of masked convolution plus carefully designed RNN transitions captures local and global dependencies in an autoregressive manner.

Row and diagonal LSTM variants

The earliest version of PixelRNN used a "naive" 2D LSTM, in which each hidden state depended on , , and the current pixel . Though conceptually appealing, this approach is difficult to parallelize because you essentially have to compute the entire row or column in sequence before moving on.

RowLSTM

In RowLSTM, the hidden state at position (i, j)\) is computed using only the three hidden states from the row above:

Note that the left neighbor (i, j-1)\) of the same row does not directly feed into this recurrence, thereby reducing dependencies and allowing more parallelization. Specifically, for each row , you can compute in parallel across different values, because none of them depends on each other. You only need the row . The trade-off is that you lose some immediate horizontal context, which can degrade the final image quality. However, this approach is significantly faster and simpler to implement on modern GPU hardware.

Diagonal BiLSTM

Diagonal BiLSTM tries to recover more local context by using a diagonal scanning procedure. Conceptually, each diagonal in the image is processed in parallel, so that the state depends on and . The trick is that, rather than scanning row by row, you shift each row (or equivalently, shift the image) so that the relevant computations line up in columns, enabling parallel calculation across diagonals. This yields better image quality because both the "above" pixel and the "left" pixel are integrated. However, the parallelization strategy is more complex than in RowLSTM, and the computational overhead can be higher.

The LSTM update itself follows the standard formulation:

where is the state-to-state convolution kernel, is the input-to-state kernel, denotes convolution, denotes elementwise multiplication, and is typically the sigmoid activation function. The difference between RowLSTM and Diagonal BiLSTM is simply in how or is indexed and how parallelization is arranged across the image.

Training procedure and loss function

Because these are autoregressive models that predict discrete pixel values (e.g., 0–255 per channel in an 8-bit image), the typical loss is the negative log-likelihood (often implemented as a cross-entropy). Concretely, for each pixel location , the model outputs a probability distribution over possible values. The training objective is then to minimize:

averaged over all images in the training dataset. This direct log-likelihood training is stable and does not require an adversary or other specialized optimization method. In practice, large minibatches or specialized GPU parallelization are used to handle the many computations across large image datasets.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths:

- Stable training: Because the model is optimized via a direct log-likelihood objective, there's no need to solve complicated equilibrium conditions (unlike GANs).

- Accurate density estimation: PixelRNN provides an explicit estimate of . You can compute log-likelihoods and interpret them as probabilities.

- Good coverage: Autoregressive models tend not to suffer from mode collapse as severely as some adversarial approaches might.

Limitations:

- Slow sampling: Generating an image is a sequential process, especially in RNN-based approaches. You must predict each pixel in turn.

- Potentially large memory footprint: Each RNN step processes a hidden state that must be stored and updated, which can be expensive for large images.

- Less photorealistic than advanced GAN-based or diffusion-based methods for many tasks, although the gap is narrower for some image domains.

Next, let us examine PixelCNN, an approach that trades some of the recurrent overhead for purely convolutional operations with carefully designed masks.

PixelCNN

Network design

Where PixelRNN leans on LSTM or recurrent variants to incorporate context from previously generated pixels, PixelCNN uses masked convolutional layers to accomplish the same objective. Instead of scanning row by row with RNN steps, PixelCNN processes the entire image in parallel using special convolution masks that "block out" the future pixels.

- Masked Convolution (MaskA) for the first layer to ensure the model does not peek at the current pixel or future channels.

- Additional MaskB-type layers in deeper parts of the network, allowing partial context from already processed color channels in the same pixel, but still preventing access to future positions.

- Stack of convolutional layers that repeatedly expand the receptive field while ensuring no future positions are visible.

- Dimension-reduction blocks (optional) to handle large images, typically downsampling the spatial resolution partway, then upsampling again, reminiscent of certain U-Net or autoencoder-like structures.

- Final convolution to map hidden features to pixel-intensity logits, followed by a Softmax for discrete distribution output (or a mixture of logistics for real-valued intensities).

Why convolution? Convolutions are well-suited to capturing local spatial structure, and they can be executed in parallel across the entire image on modern hardware. By carefully applying masks, you can force the network to respect the autoregressive ordering. This is typically simpler and more parallelizable than an RNN-based approach.

An image was requested, but the frog was found.

Alt: "MaskA and MaskB used in PixelCNN"

Caption: "Two types of masks in PixelCNN ensure the network does not peek at future pixel positions."

Error type: missing path

Masked convolutions in PixelCNN

Recall the difference between MaskA and MaskB:

- MaskA: For the very first convolution, we ensure that the current pixel's values (or current channel) is excluded from the receptive field. If you are generating color channels in the order (Red -> Green -> Blue), then for the red channel of pixel , the mask zeros out any weights that would see that same pixel's red channel. For the green channel, the mask must zero out the future position in the green plane but can see the red channel. This ensures no "leaking" of information from the present pixel's green or blue channel into the distribution for the red channel.

- MaskB: In deeper layers, we slightly relax the restriction so that the network can see what has already been generated in the same channel. In effect, MaskB includes the entire receptive field from previous channels plus the currently processed channel up to the position in the flattened ordering. This enables deeper layers to combine more context and refine predictions.

Conditional PixelCNN variants

One can easily condition PixelCNN on additional information by injecting some representation (e.g., a class label, a text embedding, or latent features from another network) into each convolutional block. This is typically done through additive or multiplicative gating at the hidden layers, or by concatenating the conditioning as extra feature maps. For example, in a class-conditional PixelCNN, the network can incorporate a one-hot class vector at each layer, effectively learning separate generative pathways for each class.

Receptive fields and pixel dependencies

As you stack more masked convolution layers (with standard kernel sizes like or ), the receptive field for each pixel grows, eventually encompassing the entire region of "past" pixels from the top-left corner to the current pixel location. By adding skip connections or residual blocks, the network can preserve features learned at various scales, further enriching the model's capacity.

Training and sampling strategy

Training is analogous to PixelRNN: we minimize the negative log-likelihood. In practice, PixelCNN is typically easier to train on GPUs compared to PixelRNN due to fully convolutional parallelization. The typical training objective remains:

The difference is that for each forward pass, the entire image is processed in parallel through masked convolutions.

For sampling, we still have a sequential dependency in concept (we must generate pixels left-to-right, top-to-bottom), but now each new pixel can be updated in a single pass of the CNN. Concretely:

- Initialize an empty image (all zeros or random noise).

- For each pixel in raster-scan order:

- Feed the partially generated image into the PixelCNN.

- Read off the distribution over possible values for the current pixel.

- Sample from that distribution (e.g., pick a random value from the predicted categorical distribution).

- Place that value in the image and move on to the next pixel.

Although we conceptually proceed in a pixel-by-pixel manner, each pixel's distribution can be computed fairly quickly because the CNN processes all positions in one pass, ignoring only future pixels via the mask. Still, it remains an inherently sequential process: you can't finalize pixel without having assigned a value to .

Key benefits

- Parallelizable: Much better GPU utilization during training compared to PixelRNN.

- Stable likelihood training: As with all autoregressive models, you get a well-defined log-likelihood objective.

- Flexible conditioning: Easy to incorporate side information, such as class labels or partial images.

However, the speed at inference time is still not as fast as feed-forward generative models (e.g., certain types of VAEs or large diffusion models with specialized sampling strategies). Yet for certain tasks where explicit density estimation is crucial, PixelCNN remains a strong contender.

Comparison of PixelRNN and PixelCNN

Performance metrics

PixelRNN and PixelCNN are often evaluated on likelihood-based metrics such as bits per dimension (bpd) on standard image datasets like CIFAR-10 or ImageNet. They can also be qualitatively evaluated by the diversity and quality of samples. Typically, PixelRNN shows good performance in capturing complex dependencies, sometimes providing slightly better likelihood scores, but PixelCNN is usually not far behind (and in some cases is even better with advanced variants like Gated PixelCNN or PixelCNN++).

Computational complexity

- PixelRNN:

- Potentially slow unrolling across the entire image, especially for large images.

- RowLSTM and Diagonal BiLSTM partially mitigate this, but parallelization remains tricky.

- PixelCNN:

- Very parallelizable on modern GPUs.

- Each convolution operation can process all positions in the image simultaneously, subject to the masked constraints.

In practice, PixelCNN is often favored for large-scale experiments because its parallel convolution architecture is more straightforward to implement efficiently.

Image quality and diversity

- PixelRNN can capture dependencies in both vertical and horizontal directions using recurrent connections, sometimes resulting in slightly sharper or more coherent images for certain domains.

- PixelCNN can produce comparable results, and in some improved variants (like Gated PixelCNN or PixelCNN++), the quality is often on par with or better than PixelRNN.

- Both remain outperformed in sheer image realism by certain advanced implicit generative models (e.g., large-scale diffusion or certain well-tuned GANs). However, they produce explicit likelihood estimates, which is a valuable property for tasks like density estimation, anomaly detection, or image compression research.

Practical considerations

- Memory usage: PixelRNN variants with many LSTM layers can become memory-intensive. PixelCNN is typically more memory-efficient, though large convolutional layers can also be expensive.

- Ease of implementation: Many open-source frameworks provide sample code for PixelCNN-like masked convolutions. Recurrent structures with row or diagonal scanning are slightly more specialized but also well supported.

- Interpretability: Both approaches yield straightforward probabilities for each pixel. This can be used to measure how "surprising" a pixel is under the learned distribution.

Gated PixelCNN: PixelCNN++

Gated PixelCNN introduced a gating mechanism in the convolutional layers, reminiscent of LSTM gating, to help the model learn more nuanced dependencies. PixelCNN++ goes further by employing:

- Discretized logistic mixture output instead of a straightforward softmax for each pixel intensity.

- Variable dilation in convolutions to expand receptive field more rapidly.

- Additional architectural enhancements (skip connections, better residual blocks).

These refinements often lead to improved likelihood scores and sample quality, making PixelCNN++ a compelling alternative to PixelRNN.

Parallelization techniques

Recent research has looked into ways to parallelize the sampling process. For PixelCNN, sampling is inherently sequential in the pixel dimension, but certain "orderless" or "block-wise" approaches partially accelerate sampling by generating multiple pixels at once in a carefully orchestrated manner. Alternatively, one can compromise the strict autoregressive ordering to gain some speed in practice, though this might degrade log-likelihood performance.

Implementation

Below is a simplified example of how one might implement a PixelCNN-like model in PyTorch. This demonstration is purely illustrative and omits advanced features such as gating, skip connections, or color conditioning. It shows how to define a masked convolution layer and stack them into an autoregressive network.

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

import torch.nn.functional as F

class MaskedConv2d(nn.Conv2d):

def __init__(self, in_channels, out_channels, kernel_size, mask_type='A',

color_channels=1, padding=1):

super().__init__(in_channels, out_channels, kernel_size, padding=padding, bias=True)

# 'mask_type': 'A' or 'B'

self.mask_type = mask_type

self.register_buffer('mask', torch.ones_like(self.weight.data))

# Build the mask

# The center pixel of the kernel is at (kernel_size//2, kernel_size//2)

# We want to zero out weights that correspond to future pixels.

kh, kw = self.kernel_size

yc, xc = kh // 2, kw // 2

for y in range(kh):

for x in range(kw):

# If we are beyond the center in the x direction or the same pixel

# and mask_type='A' => zero out

if (y > yc) or (y == yc and x > xc):

self.mask[:, :, y, x] = 0

# For color images with multiple channels, handle the partial channel ordering:

# (In more advanced code, you'd zero out the weights corresponding to future color channels)

if self.mask_type == 'A':

# For Mask A, zero out the center pixel as well

self.mask[:, :, yc, xc] = 0

def forward(self, x):

self.weight.data *= self.mask

return super().forward(x)

class SimplePixelCNN(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, in_channels=1, hidden_channels=64):

super().__init__()

# First masked conv (Mask A)

self.conv1 = MaskedConv2d(in_channels, hidden_channels, kernel_size=3, mask_type='A')

# Subsequent masked convs (Mask B)

self.conv2 = MaskedConv2d(hidden_channels, hidden_channels, kernel_size=3, mask_type='B')

self.conv3 = MaskedConv2d(hidden_channels, hidden_channels, kernel_size=3, mask_type='B')

# Final layer -> produce logits (for each possible pixel intensity or continuous params)

self.output = nn.Conv2d(hidden_channels, 256, kernel_size=1) # For 256 intensities

def forward(self, x):

# x is [batch_size, 1, height, width]

x = F.relu(self.conv1(x))

x = F.relu(self.conv2(x))

x = F.relu(self.conv3(x))

x = self.output(x)

return x # shape: [batch_size, 256, height, width]

This snippet showcases:

- MaskedConv2d: A custom 2D convolution that zeroes out weights corresponding to future pixels based on the mask type.

- SimplePixelCNN: A straightforward stack of masked convolutions, culminating in a convolution that predicts logits for 256 discrete values per pixel (for a grayscale image).

- Forward pass: Each convolution is activated with ReLU, and the final layer produces the distribution from which we can compute cross-entropy loss with the ground truth pixel intensities.

A similar approach can be adapted for PixelRNN by combining masked convolutions for input processing with LSTM-based modules in the middle layers. There are open-source reference implementations (e.g., official TensorFlow and PyTorch code for PixelCNN and PixelRNN) that incorporate advanced functionalities like gating, skip connections, and dimension reduction blocks.

When training, one would typically:

- Convert an image batch into integer pixel values (0–255).

- Forward-pass the images through the network to obtain logits.

- Use nn.CrossEntropyLoss (in PyTorch) or similar to compute the negative log-likelihood of the correct pixel values.

- Backpropagate and update weights.

- Evaluate with bits per dimension or negative log-likelihood on a validation set to track progress.

Applications and use cases

PixelRNN and PixelCNN are often overshadowed by newer generative models for purely photorealistic generation. Nonetheless, they offer unique advantages in certain contexts:

-

Density estimation and anomaly detection

Because these methods produce an explicit , we can evaluate how "likely" a given image is under the model. This can be leveraged for anomaly detection, outlier detection in images, or novelty detection in medical imaging, where you might want to measure how "unusual" a new scan is relative to known healthy ones. -

Conditional image generation (inpainting, colorization, super-resolution)

If we partially observe an image (e.g., a rectangular region is missing), PixelRNN/PixelCNN can sample from the conditional distribution of missing pixels. The masked convolution approach translates readily to tasks like inpainting or colorization, where a portion of the image (or color channel) is known and the rest must be predicted. -

Image completion and extension (outpainting)

Autoregressive models can be used to extend the borders of an image in a natural-looking way. This is sometimes referred to as "outpainting," and the model's knowledge of local context can yield interesting expansions of the original scene. -

Artistic or stylized generation

While PixelRNN/PixelCNN might not surpass more advanced generative models in photorealism, they can still produce interesting creative or stylized samples. They can also be combined with other approaches or used to generate texture-like images with strong local dependencies. -

Research in probability modeling

PixelRNN/CNN remain strong baselines for log-likelihood-based generative modeling research. They're widely used to compare new ideas in architecture or training objective against a known, well-understood approach.

An image was requested, but the frog was found.

Alt: "Faces generated via PixelCNN"

Caption: "Faces generated using a PixelCNN-like architecture (courtesy of published research on Natural Image Modeling)."

Error type: missing path

Beyond these direct applications, PixelRNN and PixelCNN have inspired a number of subsequent breakthroughs. For instance, WaveNet (van den Oord and gang, 2016) for audio generation was directly influenced by the success of PixelCNN, adapting masked convolutions for one-dimensional waveforms. Similarly, the concept of masked convolution is key in modern Transformer-based architectures for language modeling (where they use "causal" attention masks).

Extra remarks (no formal conclusion)

PixelRNN and PixelCNN exemplify the power of autoregressive modeling for images. While they no longer represent the cutting edge of generative image quality, their conceptual clarity, explicit likelihood training, and widespread reference implementations have made them enduringly relevant in deep learning curricula and research. Moreover, advanced improvements such as Gated PixelCNN, PixelCNN++, or hybrid approaches that combine recurrent and convolutional blocks continue to push the boundaries of purely autoregressive image synthesis.

You can find open-source implementations to study further:

An image was requested, but the frog was found.

Alt: "GAN vs. PixelCNN sample comparison"

Caption: "GAN-synthesized faces often appear more photorealistic than typical PixelCNN outputs, but PixelCNN provides stable training and explicit density."

Error type: missing path

Ultimately, these approaches highlight the broader principle that local dependencies and proper factorization are crucial to generative modeling of high-dimensional data like images. Whether you reach for an RNN or a CNN, the idea of carefully restricting the model's receptive field so it only sees "past" pixels is essential to ensure correct autoregressive training.

In practice, if you desire maximum photorealism, you might opt for a powerful diffusion model or a well-tuned GAN. If, however, you need stable log-likelihood estimation, the ability to do outlier detection, or an interpretable measure of how well a model "understands" each pixel, PixelRNN and PixelCNN remain superb educational and practical tools.