🎓 100/168

This post is a part of the Computer vision educational series from my free course. Please keep in mind that the correct sequence of posts is outlined on the course page, while it can be arbitrary in Research.

I'm also happy to announce that I've started working on standalone paid courses, so you could support my work and get cheap educational material. These courses will be of completely different quality, with more theoretical depth and niche focus, and will feature challenging projects, quizzes, exercises, video lectures and supplementary stuff. Stay tuned!

Neural style transfer (NST) is a remarkable method in the domain of deep learning and artistic image processing that re-synthesizes an input image to match the style of another image while retaining the original content. In other words, the goal is to produce a single, new image that simultaneously resembles the structure of a "content image" (often a photograph) and the visual aesthetics — or painterly style — of a separate "style image" (for instance, a famous artwork). The procedure leverages deep convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and their learned feature representations to disentangle the concept of content from that of style.

Historically, neural style transfer is most commonly associated with Gatys and gang (2015) who introduced a pioneering approach that formulated the style transfer task as an iterative optimization problem on the pixel space of an initially random image, guided by carefully designed style and content loss functions. The basic concept was that the deeper layers of a pre-trained network capture semantic and structural (content) information, while the correlations among activation channels represent the stylistic or texture-based aspects.

Before neural networks were exploited for style transfer, researchers in computer graphics were exploring non-photorealistic rendering (NPR) approaches designed to produce painterly, cartoon-like, or otherwise stylized visuals from input photographs. NPR methods — such as stroke-based rendering (SBR), region-based techniques, and example-based rendering — had some success but were often hand-engineered for specific artistic styles (like watercolor or oil painting). They struggled to generalize to arbitrary styles. Moreover, they often lacked a mechanism to systematically capture and re-synthesize complex patterns found in arbitrary reference paintings.

Neural style transfer revolutionized the field by providing a framework wherein a deep CNN (often trained on a vast classification task like ImageNet) can serve as a powerful feature extractor. Through specific loss functions that encourage matching high-level content features to the content image, and second-order statistical measures (e.g., Gram matrices) to the style image, one can iteratively update an initially random image until it meets both content and style criteria. The result is an image that looks strikingly like an artwork painted with the subject matter of the original photograph.

In modern machine learning, neural style transfer is recognized as an important stepping stone, not only for interesting aesthetic applications — such as turning a video or photo into the style of van Gogh or Monet — but also as a demonstration of how CNN layers can encode different levels of abstraction and how these encodings can be manipulated in a generative manner. It also provided significant motivation for a variety of follow-up methods that accelerate style transfer, expand it to real-time applications, or adapt it to new domains such as audio, video, and 3D content.

Below, I discuss the fundamental concepts behind NST, ranging from the idea of content and style representations to the ways we can formulate the optimization. I then present popular models and algorithms in the field, together with advanced or hybrid methods that keep emerging. I also dive into practical implementation details — covering frameworks, pretrained networks, hyperparameter selection, and strategies to address computational bottlenecks. Finally, I examine the breadth of real-world applications, typical challenges, and known limitations that will guide you in understanding how to use and expand these techniques in your own data science and research endeavors.

Core mathematical foundations

2.1 content and style representations

A neural network trained for large-scale image classification on a dataset such as ImageNet learns hierarchical features that progress from low-level edges and color blobs in early layers to more sophisticated shapes and object parts in intermediate layers, and finally to complex object concepts in deeper layers. Neural style transfer exploits this representational power to capture the distinct ideas of "content" and "style" from separate images.

-

Content representation:

- The assumption is that deeper layers of a CNN focus more on semantic information and less on exact pixel placements. For example, a deeper convolutional block might produce high activation values when it identifies that an image contains a dog, or that there is a certain shape in a specific region.

- Let denote a content image and a generated image (initially random noise or a copy of ) that we will iteratively update.

- If we pass both and through the same pretrained network and extract their feature maps at a deeper layer , we obtain two activations: and . The content loss then measures how different these two sets of activations are.

-

Style representation:

- The style of an image is often characterized by textural cues, brushstroke patterns, repeated motifs, or color distributions. Rather than focusing on how each pixel lines up in space, style can be computed by correlations among activation channels (also known as feature maps) across particular layers.

- The Gram matrix is a classical approach used to capture these correlations. Each entry in the Gram matrix indicates how strongly two feature channels co-activate over the spatial extent of the image.

- By matching the Gram matrices of to those of a style image , we ensure that learns the overall patterns, textures, and color relationships inherent to the style image.

Although many variations exist, the standard approach is to sum a content loss term and a style loss term (each possibly aggregated over multiple layers) into a single objective function, then perform gradient-based optimization on the pixel space of .

2.2 loss functions for style and content

Let represent the content loss between the original content image and the generated image . A typical form is:

Here, and denote the feature maps (or activations) extracted at layer for images and , respectively. Indices run over the spatial dimensions and channels as needed (the exact indexing scheme may vary by implementation).

The style loss is computed by measuring how close the correlations among feature maps in are to the correlations in . For each layer designated to represent style, one forms the Gram matrix:

where is the activation map at layer arranged as a matrix of shape (with the number of channels and the spatial resolution). The style loss at layer thus becomes:

where is the number of feature maps (channels) at layer and is the number of spatial positions in each feature map. The total style loss is typically a weighted sum of the losses at selected layers:

Finally, the entire objective to minimize is:

where and are coefficients that control the trade-off between content fidelity and style faithfulness.

2.3 gram matrices and correlation of features

The Gram matrix emerges from texture modeling, where second-order statistics among filter responses capture global textural patterns. In the NST setting:

- Each element of the Gram matrix at row and column indicates how often feature map co-occurs spatially with feature map for image .

- If certain channels strongly co-activate (e.g., a channel that detects diagonal brush strokes consistently aligns with a channel that detects vibrant color smears), a large off-diagonal value arises in the Gram matrix.

- By matching the Gram matrices from and , one can recreate a similar set of textural correlations in that characterize the style image.

Gram matrices are at the heart of parametric texture models for style transfer, but we will see that non-parametric methods can also be used. In some approaches (often for more photorealistic or structurally constrained tasks), a Markov Random Field (MRF) can be leveraged to preserve local patches of style rather than global correlations.

Popular algorithms and models

Neural style transfer has branched into numerous variants, each with its own computational trade-offs, stylistic capabilities, and potential for real-time execution. Below are some canonical and influential examples.

3.1 gatys and gang's original approach

Leon Gatys, Alexander Ecker, and Matthias Bethge introduced the first well-known neural style transfer framework (Gatys and gang, 2015). Their method is image-optimization-based, meaning the output image is initialized (e.g., random noise or a copy of the content image) and then iteratively updated via gradient descent to minimize the total loss .

Key characteristics:

- Flexibility: It can handle arbitrary style images, including paintings, sketches, or even fractal-like textures.

- Computational intensity: Because every forward pass of through the CNN requires a backward pass to compute gradients in pixel space, and because dozens or hundreds of iterations may be needed, inference can be slow.

- Seminal insight: It revealed the power of CNN feature correlations for capturing style, essentially forging a new line of research in texture modeling, generative art, and interpretability.

Despite producing compelling results, the Gatys method can be slow and sometimes struggles with preserving certain fine structures or achieving photorealistic results. Many subsequent works address these shortcomings.

3.2 fast neural style transfer (johnson and gang)

Johnson, Alahi, and Fei-Fei (2016) proposed a model-optimization-based approach in which a feed-forward generator network is trained offline so that inference (style transfer on a given content image) happens in a single forward pass. Instead of iteratively optimizing for each new input, they do the heavy lifting during an offline training phase:

- They define a similar loss function as Gatys and gang (a combination of content and style losses), but now the optimization variable is not the output image itself but the parameters of a generator network .

- Once trained, can take an arbitrary content image and produce a stylized image almost instantaneously.

Advantages:

- Real-time or near real-time style transfer on new images.

- Capability to handle high-resolution inputs efficiently after the model is trained.

Limitations:

- A separate generator must be trained for each style (or for a limited set of styles), which can be storage intensive if many different styles are desired.

- Network capacity can limit the diversity of styles, prompting multi-style or arbitrary-style expansions.

3.3 cyclegan for style transformation

CycleGAN (Zhu and gang, 2017) represents another milestone in style transformation, though it was not originally proposed solely for artistic style transfer. Rather, it is a method for unpaired image-to-image translation, learning to transform images from one domain (e.g., horses) to another domain (e.g., zebras) without requiring paired training data.

Relevance to NST:

- While Gatys-based NST typically needs a single style image to guide the transformation, CycleGAN can learn from a collection of style domain images, capturing a broader notion of the style domain.

- The cycle consistency loss introduced by CycleGAN ensures that when an image is translated from domain A to domain B and back again, it should recover the original image.

For purely artistic style transfer, CycleGAN can be used if you have a larger dataset of artworks representing a style domain. However, it is more suited to domain translation tasks — like turning day photos into night scenes, or sketches into real images — than to the single-example style capture of Gatys's method.

3.4 recent advances and hybrid methods

Since the original proposals, a vast landscape of techniques has emerged:

- Patch-based or MRF-based approaches: Instead of matching global statistics with Gram matrices (parametric models), some methods match local patches (non-parametric). These can preserve finer details or produce more realistic textures.

- Photorealistic style transfer: Researchers introduced specialized constraints that minimize distortions when the content image is a realistic photo. Approaches like Luan and gang incorporate semantic segmentations or additional regularization to achieve subtle recoloring that remains faithful to scene geometry.

- Multi-style and arbitrary-style networks: Early feed-forward models had to be trained separately for each style, but subsequent work introduced ways to handle multiple or entirely arbitrary styles in a single network — e.g., through conditional instance normalization (CIN), adaptive instance normalization (AdaIN), or learned transformations that decouple content and style features.

- Video style transfer: Additional constraints, typically in the form of temporal consistency losses, reduce flickering across consecutive frames, enabling stylized videos that remain stable over time.

Overall, the field continues to evolve. Recent research explores combining style transfer with other generative models (e.g., diffusion models or generative adversarial networks) or focusing on improved semantic matching of style to content for more sophisticated results.

Implementation details

4.1 tensorflow and pytorch

Due to its reliance on automatic differentiation and fast linear algebra, NST is easily implemented in modern deep learning frameworks such as TensorFlow or PyTorch. The fundamental workflow is:

-

Load and preprocess images (, , and the initial ).

-

Load a pretrained CNN (often VGG16 or VGG19 trained on ImageNet).

-

Define a function for computing the content loss and style loss.

-

Set up an optimizer to modify either:

- The pixels of directly (in the case of image-optimization methods), or

- The parameters of a generator network (in the case of feed-forward methods).

-

Iteratively run gradient descent until the losses converge or a certain iteration/time limit is reached.

Below, I provide a small PyTorch-based example code snippet that demonstrates the general concept of the Gatys-style approach. While the snippet is simplified, it highlights key modules such as a normalization layer, content loss, style loss, and the final optimization loop.

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

import torch.optim as optim

import torch.nn.functional as F

import copy

from torchvision import models

# Assume device, content_img, and style_img are defined elsewhere,

# and that content_img, style_img are Tensors with shape [1, 3, H, W].

device = torch.device("cuda" if torch.cuda.is_available() else "cpu")

def gram_matrix(input):

# input shape: [batch_size, num_channels, height, width]

b, c, h, w = input.size()

features = input.view(b * c, h * w)

G = torch.mm(features, features.t())

return G.div(b * c * h * w)

class StyleLoss(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, target_feature):

super(StyleLoss, self).__init__()

self.target = gram_matrix(target_feature).detach()

self.loss = 0

def forward(self, input):

G = gram_matrix(input)

self.loss = F.mse_loss(G, self.target)

return input

class ContentLoss(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, target):

super(ContentLoss, self).__init__()

self.target = target.detach()

self.loss = 0

def forward(self, input):

self.loss = F.mse_loss(input, self.target)

return input

class Normalization(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, mean, std):

super(Normalization, self).__init__()

self.mean = torch.tensor(mean).view(-1, 1, 1)

self.std = torch.tensor(std).view(-1, 1, 1)

def forward(self, img):

return (img - self.mean) / self.std

cnn = models.vgg19(pretrained=True).features.to(device).eval()

# We define a function to set up the style/content losses

def get_style_model_and_losses(cnn, normalization_mean, normalization_std,

style_img, content_img,

content_layers=['conv_4'],

style_layers=['conv_1','conv_2','conv_3','conv_4','conv_5']):

cnn = copy.deepcopy(cnn)

normalization = Normalization(normalization_mean, normalization_std).to(device)

content_losses = []

style_losses = []

model = nn.Sequential(normalization)

i = 0

for layer in cnn.children():

if isinstance(layer, nn.Conv2d):

i += 1

name = 'conv_{}'.format(i)

elif isinstance(layer, nn.ReLU):

name = 'relu_{}'.format(i)

layer = nn.ReLU(inplace=False)

elif isinstance(layer, nn.MaxPool2d):

name = 'pool_{}'.format(i)

elif isinstance(layer, nn.BatchNorm2d):

name = 'bn_{}'.format(i)

else:

raise RuntimeError(f'Unrecognized layer: {layer.__class__.__name__}')

model.add_module(name, layer)

if name in content_layers:

target = model(content_img).detach()

content_loss = ContentLoss(target)

model.add_module("content_loss_{}".format(i), content_loss)

content_losses.append(content_loss)

if name in style_layers:

target_feature = model(style_img).detach()

style_loss = StyleLoss(target_feature)

model.add_module("style_loss_{}".format(i), style_loss)

style_losses.append(style_loss)

# Trim the network after the last style/content loss

for i in range(len(model)-1, -1, -1):

if isinstance(model[i], ContentLoss) or isinstance(model[i], StyleLoss):

break

model = model[:(i+1)]

return model, style_losses, content_losses

def get_input_optimizer(input_img):

optimizer = optim.LBFGS([input_img.requires_grad_()])

return optimizer

def run_style_transfer(cnn, normalization_mean, normalization_std,

content_img, style_img, input_img, num_steps=300,

style_weight=1e6, content_weight=1):

model, style_losses, content_losses = get_style_model_and_losses(

cnn, normalization_mean, normalization_std, style_img, content_img

)

optimizer = get_input_optimizer(input_img)

run = [0]

while run[0] <= num_steps:

def closure():

input_img.data.clamp_(0, 1)

optimizer.zero_grad()

model(input_img)

style_score = 0

content_score = 0

for sl in style_losses:

style_score += sl.loss

for cl in content_losses:

content_score += cl.loss

style_score *= style_weight

content_score *= content_weight

loss = style_score + content_score

loss.backward()

run[0] += 1

if run[0] % 50 == 0:

print(f"Iteration {run[0]}:")

print(f"Style Loss : {style_score.item()} Content Loss: {content_score.item()}")

print()

return loss

optimizer.step(closure)

input_img.data.clamp_(0, 1)

return input_img

# Example usage:

# content_img, style_img = ... (some loaded images)

# input_img = content_img.clone()

# output = run_style_transfer(cnn, [0.485, 0.456, 0.406], [0.229, 0.224, 0.225],

# content_img, style_img, input_img)

In practice, you might refine the layer choices for content and style representation, or use different optimizers like Adam or plain gradient descent. Some references even find that L-BFGS can work well for the iterative approach because it converges rapidly in practice (as in the original Gatys demonstration).

4.2 pretrained networks (vgg, resnet, etc.)

VGG16 and VGG19 are the most commonly used backbone networks for NST, due to:

- Their simplicity: The architecture is quite straightforward (sequential blocks of conv and pooling layers) and easy to dissect at arbitrary layers.

- Their proven performance on large-scale image classification.

- Prior usage: The original Gatys and gang method used VGG19. This established a sort of default standard that many subsequent works followed for consistency.

Nonetheless, other networks can be substituted:

- ResNet: In principle, a ResNet-based approach can also capture content and style; some practitioners prefer it for certain tasks or to exploit skip connections.

- Inception: A broader receptive field might better capture certain global style cues, though the fragmentation of paths can complicate which layers to use for style or content.

- MobileNet: For real-time or embedded style transfer, a smaller or more efficient architecture might be beneficial.

In practice, the key is not so much the original classification performance but whether the network's intermediate layers offer useful feature hierarchies for content and style extraction. Because VGG is so well-tested in NST contexts and widely available in frameworks (with easy ways to access intermediate feature maps), it remains the standard choice.

4.3 hyperparameters tuning (learning rate, iterations, etc.)

Several hyperparameters matter in NST:

-

Learning rate:

- If it is too large, the generated image can oscillate wildly or diverge.

- If it is too small, optimization might take too long or get stuck in poor local minima.

- Typical ranges vary ��— some use to , but it depends on the optimizer, the scale of the loss, and the normalization layers.

-

Number of iterations:

- Image-optimization-based NST can require anywhere from 200 to 2000 iterations. Often, 300–500 can suffice for a stable solution.

- If you see incomplete stylization or under-fitting, increasing iteration count helps. If you see heavy distortions or excessive stylization, you might need fewer iterations or a different style weight.

-

and (the weighting factors of content vs. style):

- A large compared to yields an image heavily influenced by the style at the cost of losing content structure.

- Conversely, a large preserves content but the stylization might be weak.

-

Choice of layers:

- Typically, content is measured in deeper layers (like or in VGG).

- Style is measured in a combination of shallow and deeper layers to capture both low-level texture and high-level structural patterns.

Each style image can have unique demands. Some require focusing on color distributions in earlier layers; others need more abstract representations from deeper layers. Experimentation or references to previous findings often guide these choices.

4.4 optimization strategies (gradient descent, l-bfgs, etc.)

- Gradient Descent (GD): A basic approach, typically with a certain learning rate and momentum or Adam-based updates.

- L-BFGS: A quasi-Newton method often used in the original Gatys code. It tends to converge quickly in practice for style transfer, though it can require more memory.

- Feed-forward networks: For real-time style transfer, the entire iterative optimization (style + content losses) is effectively done offline to train a generator network. At inference time, no iterative pixel update is needed.

Each method has trade-offs in speed, memory usage, and ease of tuning. If you are performing style transfer for a single piece of content, a direct iterative approach can be simpler. But if you need to stylize thousands of images, investing in a feed-forward solution might be more cost-effective.

4.5 handling computational constraints

Neural style transfer can be computationally expensive, especially at higher resolutions. Some strategies to manage computational load:

- Starting with a smaller image: For faster experimentation, reduce the resolution of the content (and style) images. You can later run a higher-resolution pass if needed.

- Using fewer layers: Instead of measuring style at many convolutional blocks, reduce the number of style layers.

- Gradient checkpointing: For large networks, you can reduce memory usage by re-computing some intermediate activations on-the-fly.

- Mixed precision: Running in half precision (e.g., FP16) can accelerate computations on modern GPUs.

- Efficient architectures: If training a feed-forward model, consider using a smaller generator network or a mobile-optimized backbone.

4.6 additional implementation notes and advanced code examples

Beyond the minimal code, many advanced details can be included:

- Instance Normalization vs. Batch Normalization: Ulyanov and gang found instance normalization beneficial for style transfer.

- Multilayer perceptron (MLP) predictions of style parameters: In multi-style networks, you might feed an embedding of the style image into an MLP that generates normalization or scaling parameters for the generator.

- Loss weighting schedules: Some approaches linearly ramp or gradually decrease style or content weights over iterations to produce more stable training.

These details can significantly influence the quality of your final stylized image or the efficiency of training.

Applications, limitations, challenges

Neural style transfer is visually striking, but practical usage in industry or research can present unique challenges. Below are common scenarios, pitfalls, and expansions.

-

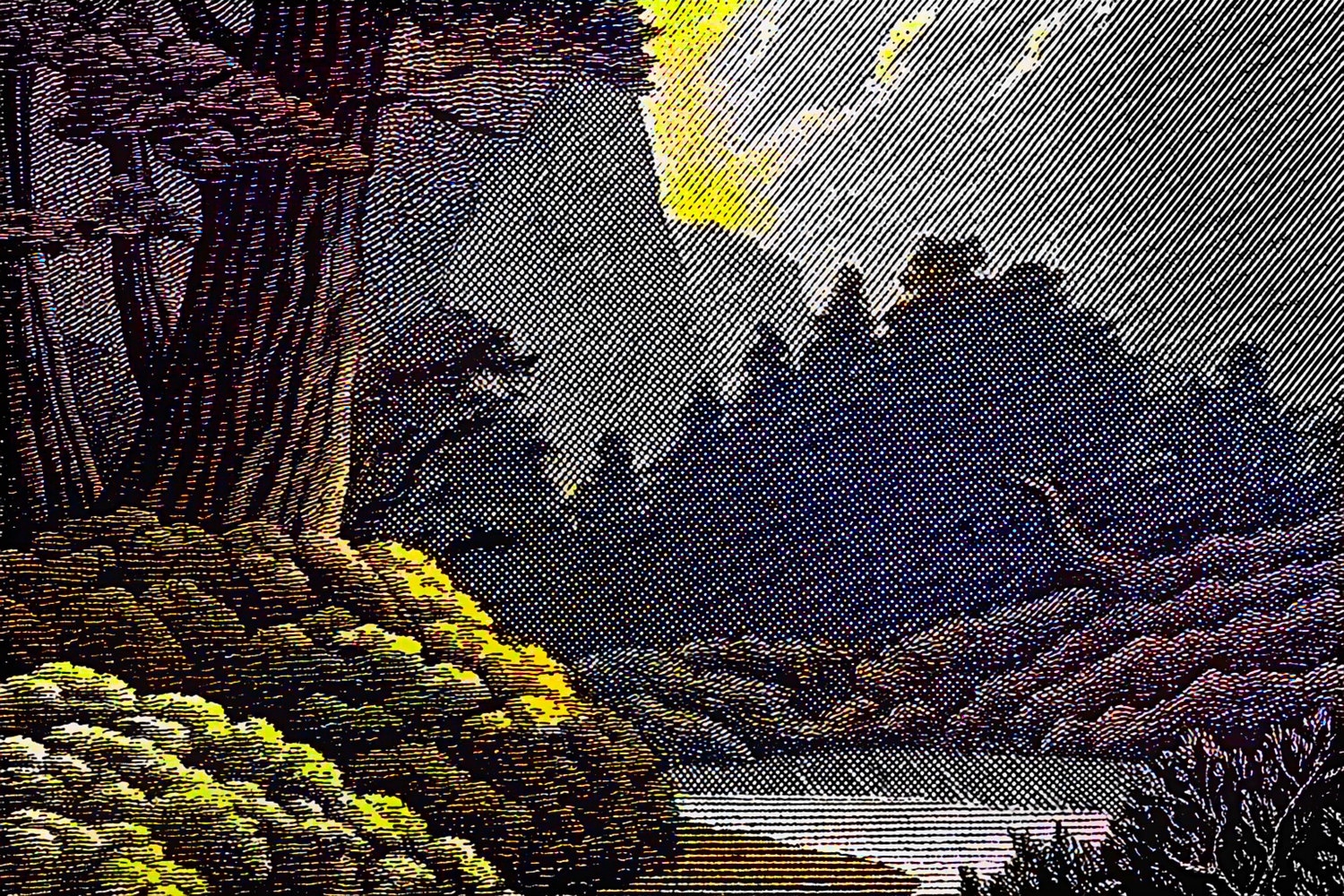

Artistic transformations and design

- Turning photographs into stylized versions reminiscent of classical paintings (e.g., van Gogh's Starry Night).

- Tools used by photographers and artists to produce unique filters or textures.

- Interactive applications let the user pick different styles in real time.

-

Photo and video stylization

- Entire video sequences can be stylized for commercials, music videos, or short films.

- Achieving temporal consistency is critical. Flickering or color shifts from frame to frame degrade the user experience.

- Some frameworks implement optical flow constraints or multi-frame architectures.

-

Commercial and marketing use cases

- Advertisements that incorporate a brand's signature aesthetic or well-known painting style.

- Novelty services that transform user-uploaded content into stylized prints, postcards, or T-shirt designs.

-

Real-time interactive tools

- Mobile apps or web-based demos that apply filters to live webcam feeds.

- Platforms for user-driven content creation in gaming or social media.

-

Computational cost and hardware requirements

- High-resolution images demand more GPU memory and longer optimization times.

- Real-time performance typically requires a dedicated feed-forward approach or specialized hardware (e.g., GPU acceleration, FPGA).

- Large style networks might be impractical for deployment on edge devices unless carefully compressed or quantized.

-

Resolution and output quality

- Going beyond typical 512x512 or 1024x1024 images can drastically slow training/inference.

- Larger outputs often require carefully tuned hyperparameters to maintain content fidelity.

-

Balancing style and content integrity

- Over-stylization can obscure the original shapes or degrade essential content.

- Under-stylization can result in an image that looks too much like the original.

- Tuning and is partially subjective and often style-dependent.

-

Sensitivity to complex patterns and textures

- Some style images involve extremely intricate patterns (e.g., fractals or abstract swirling lines). The generated image can show repeated artifacts or fail to capture subtle color transitions.

- Conversely, extremely simple style images might not transform the original content significantly.

-

Visual artifacts and distortions

- Seams or patch boundaries in patch-based methods (MRF approaches).

- Color drift where the color palette of the style is over-applied or shifts undesirably.

- Deformed geometry in certain areas if the style includes strong edges that conflict with the shapes in the content.

Nevertheless, neural style transfer remains a high-impact demonstration of deep neural networks' ability to manipulate high-level features in images. Evolving research addresses issues such as semantic alignment, user control over specific regions of style transfer, and memory or computational constraints.

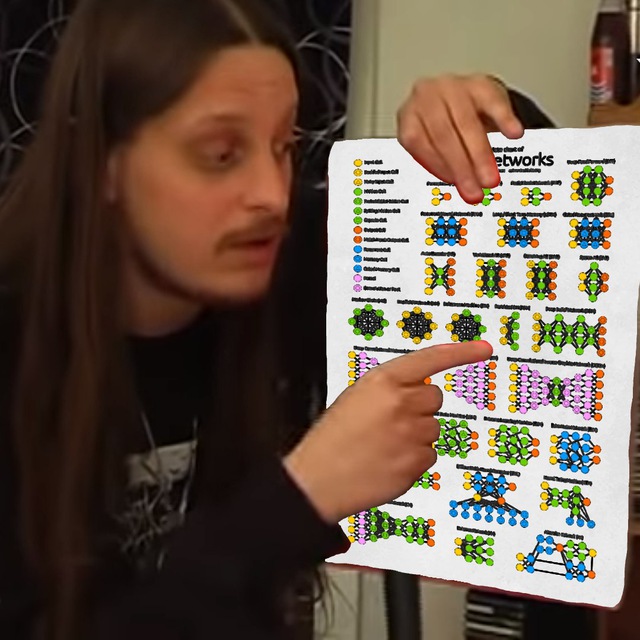

Below is an optional placeholder image to illustrate the concept of extracting content from one image and style from another:

An image was requested, but the frog was found.

Alt: "Neural style transfer diagram"

Caption: "High-level schematic of neural style transfer showing separate content and style images, with a CNN extracting relevant features from both to guide the generation of a new stylized output."

Error type: missing path

By walking through the rationale, mathematics, and practical considerations, one can see why neural style transfer is widely studied and utilized in advanced data science and machine learning contexts. The synergy between deep neural representations and classical texture modeling (via Gram matrices or other methods) remains a fascinating intersection of artistry, signal processing, and cutting-edge neural architectures.

Whether you are building an application for real-time mobile stylization or generating high-resolution prints, an in-depth understanding of how content and style are mathematically extracted and combined will significantly improve your ability to tune hyperparameters, choose network architectures, and interpret the strengths and limitations of neural style transfer algorithms.