🎓 35/2

This post is a part of the Clustering basics educational series from my free course. Please keep in mind that the correct sequence of posts is outlined on the course page, while it can be arbitrary in Research.

I'm also happy to announce that I've started working on standalone paid courses, so you could support my work and get cheap educational material. These courses will be of completely different quality, with more theoretical depth and niche focus, and will feature challenging projects, quizzes, exercises, video lectures and supplementary stuff. Stay tuned!

Clustering is a fundamental technique in the realm of unsupervised learning and exploratory data analysis. Whether someone employs it for customer segmentation, anomaly detection, document grouping, image compression, or biological data analysis (e.g., grouping gene expression profiles), clustering unveils hidden structures and natural groupings in unlabeled datasets. Despite its ubiquitousness and broad application, evaluating the quality of a clustering solution can be surprisingly tricky. After all, clustering is typically an exploratory procedure; there are no known "true" labels or ground truths in many real-life scenarios.

Many sophisticated clustering methods exist — for example, K-means, DBSCAN, hierarchical clustering, Gaussian mixture models, spectral clustering, mean shift, density-based approaches, among others — and each of these algorithms can produce significantly different partitions of a dataset. Even with the same algorithm, slight variations in hyperparameters (e.g., number of clusters , distance metrics, density thresholds, or initialization seeds) might cause widely different clustering outcomes. As a result, to systematically compare and select appropriate clustering methods and parameters, we need robust, interpretable, and mathematically grounded metrics. These metrics, referred to collectively as clustering validity indices or clustering metrics, can guide practitioners in diagnosing whether a particular clustering effectively captures meaningful structure in data.

However, clustering metrics present unique challenges that are not as severe in supervised learning tasks like classification. In classification, we usually have well-defined target labels, so we can measure the discrepancy between predictions and known truths. In clustering, we often do not have such ground truth labels. Even if some reference partition is available, we might only treat it as a partial or noisy approximation of the "real" underlying structure, which is not necessarily absolute.

From a theoretical perspective, Kleinberg's impossibility theorem: there's no single clustering function that satisfies all properties (scale invariance, richness, consistency) simultaneously. indicates that no single approach to clustering — and by extension, no single clustering metric — can be considered perfect and universally optimal under all conditions. Instead, a wide array of internal and external metrics have been devised. Each of them provides its own vantage point to assess the quality of a clustering outcome.

Goal of this article:

This text aims to deliver an extensive tutorial-style exploration of the main clustering metrics, from classical measures like Silhouette Coefficient, Sum of Squared Errors (SSE), and Rand Index, to more specialized or lesser-known ones such as the Minkowski Score, Variation of Information, or the Score Function index. We will cover both internal and external approaches in detail, explore how one chooses a metric in practice, discuss pitfalls and advanced considerations (especially with high-dimensional data and domain-specific constraints), and present some Python-based implementations to showcase practical usage. I intend to harmonize advanced theoretical insights with enough clarity to keep the topic approachable.

Clustering evaluation is a vital skill for data scientists, ML engineers, and researchers, especially those seeking to understand or interpret the structure within their data, compare multiple algorithms, or fine-tune hyperparameters for real-world applications. By the end of this article, you will have the theoretical and practical foundations to pick and use various clustering metrics effectively.

Before diving into the metrics themselves, here are key points to keep in mind:

- Internal vs. External: Internal metrics rely solely on the data points and the resulting clusters. External metrics measure how well clusters align with external labels or external knowledge about the data.

- No universal best: A single metric might be excellent for one dataset or domain but misleading for another. The choice depends on the shape of the data, the number of clusters, the type of distance or similarity used, and domain constraints.

- Complex behavior: Many internal metrics aim to capture both the compactness of clusters (intra-cluster similarity) and their separation (inter-cluster dissimilarity). But the trade-off between these two aspects is not always straightforward and can behave differently for different cluster shapes or densities.

- Computational complexity: Certain metrics involve pairwise distance calculations and can be costly to compute for large datasets. Others scale better with the number of data points.

- Domain knowledge: No purely numerical measure should be considered final without domain considerations. Users should always interpret results in the context of the practical problem they are trying to solve.

With that in mind, let's begin our journey by discussing internal clustering metrics, which evaluate clustering quality only through the structure of the data itself.

Internal clustering metrics

When no ground truth or external reference partition is available, we turn to internal clustering metrics. These rely exclusively on the characteristics of the final clusters and the original dataset. Typically, they quantify some measure of:

- Cluster cohesion (a.k.a. compactness): How close together the points within the same cluster are.

- Cluster separation: How distinct or distant different clusters are from each other.

The general principle is that better clusterings should have "tight" clusters whose points are close together, and "well-separated" clusters that are far from each other. Of course, these notions can be mathematically instantiated in many ways, leading to different indices.

Below, I will describe several widely used internal metrics. Where relevant, I will also include references to advanced or specialized metrics that sometimes appear in academic research. As we go, keep in mind that each metric has different assumptions about geometry, density, or distance definitions.

Silhouette coefficient

Perhaps one of the most classical and intuitive internal metrics is the Silhouette coefficient (or Silhouette score). For each data point in cluster , the Silhouette approach compares:

- = The average distance between and all other points in its own cluster .

- = The minimum average distance between and the points of any other cluster , .

We then calculate the Silhouette value for point :

The Silhouette for the entire clustering is the average of across all points:

- A score close to indicates that points are well-matched to their own cluster (small ) and clearly distinct from other clusters (large ).

- A score near indicates overlapping clusters or ambiguous assignment.

- Negative values (less than ) suggest that a point is actually closer to a different cluster than to its own, revealing misassignment or poorly separated clusters.

The Silhouette coefficient is conceptually simple, but it can become computationally expensive ( for naive implementations) because it often requires pairwise distance calculations among all points. For large datasets, approximate or faster versions may be employed. Nonetheless, Silhouette remains a go-to metric, especially for comparing different values in algorithms like K-means.

Sum of squared errors (SSE, within-cluster sum of squares)

Another classic approach is to measure how tight each cluster is around its centroid or mean. This is common in K-means clustering, where one typically monitors the within-cluster sum of squares (SSE) during training. SSE is defined by:

where is the centroid of cluster , and denotes some distance metric, often Euclidean distance. Lower SSE indicates tighter clusters. However, SSE alone does not account for separation between different clusters, so there's no direct penalty if clusters are close to each other.

A related measure, the between-cluster sum of squares (BSS), can measure the separation from the overall mean:

where is the global mean of the entire dataset. Because of the total sum of squares, TSS = WSS + BSS, some practitioners look at the ratio or to incorporate both compactness (WSS) and separation (BSS). Nonetheless, SSE remains a simpler measure, widely used as a fundamental cost function in K-means.

Calinski–Harabasz index

The Calinski–Harabasz index (CH index) is another popular internal measure that explicitly balances the ratio of between-cluster dispersion to within-cluster dispersion. Formally:

Here, is the number of points in cluster , is the centroid of cluster , is the total number of clusters, and is the total number of data points. A higher CH value indicates more distinct clusters that are each internally cohesive and collectively well separated from the global centroid . This index typically grows with better clustering quality, with no strict upper bound.

In practice, one can compute the Calinski–Harabasz index for different and pick the that yields the highest CH value. This method is commonly used as a data-driven approach to choosing the number of clusters.

Davies–Bouldin index

Introduced in 1979 by D. L. Davies and D. W. Bouldin, the Davies–Bouldin (DB) index is among the most frequently cited internal clustering indices. It aims to measure how similar each cluster is to its most similar cluster, relative to the distance between them. It is computed as:

where

is a measure of the average dispersion or spread of points around the centroid . The DB index should be minimized. A smaller value indicates less within-cluster scatter and more distance between cluster centroids. Some variants like modify how the index handles the maximum and minimum distances between clusters.

One reason for the popularity of Davies–Bouldin is that it is relatively simple to implement and interpret, and it can handle different cluster shapes. Its computational complexity can be around in certain implementations, depending on how nearest-cluster searches are optimized.

Other notable internal metrics

Research has produced a wide variety of internal indices beyond the commonly cited ones. Below is a short sampling that may be encountered:

- Dunn Index: One of the earliest internal measures to incorporate the ratio of minimal inter-cluster distance to maximal intra-cluster diameter. However, its naive computation can be expensive (), and definitions differ in various papers.

- C-Index: This measures a form of normalized intra-cluster distance. It is minimized by clusterings with lower intra-cluster distances. Some variants have an extra factor for separation.

- S: Balances cluster variance (i.e., standard deviation within clusters) with an assessment of how "densely" clusters are separated. It can yield robust results, though implementing it can be somewhat involved.

- Score Function (SF): Proposes an exponential-based ratio of between-cluster dispersion to within-cluster dispersion, often used in certain specialized tasks.

- Minkowski Score: A rarely used but mathematically interesting index. It looks at combinatorial aspects (such as style computations) in external contexts, but can also be adapted internally in some literature.

- Gamma Index and COP Index: Both revolve around aspects of pairwise distances and separation. The Gamma Index tries to see how many cross-cluster pairs have distances less than or greater than intra-cluster pairs, while COP uses a ratio of average within-cluster distances to a measure of separation from the nearest out-of-cluster points.

- Sym-based Indices (SymDB, SymD, etc.): These are symmetrical adaptations of existing indices like DB and Dunn, which incorporate symmetry distance measures within clusters. They may be relevant in advanced research contexts.

The bottom line is that no single internal metric is guaranteed to outperform all others across every possible dataset. Different metrics highlight different cluster qualities or shapes (e.g., elongated clusters vs. spherical ones). Practitioners often compute multiple internal metrics in tandem and then apply domain knowledge.

External clustering metrics

In some cases, domain experts have partial or complete external knowledge about how data might be grouped, or they can access an external set of labels. These labels might not be "perfectly correct," but they represent an external "ground truth" or reference partition. External clustering metrics compare the clustering outcome to that reference, measuring alignment or discrepancy.

Where an external labeling truly indicates the structure you care about, external metrics can be a powerful tool to evaluate clustering performance. For instance, in gene expression data, if we have known classes for certain cell types, we can measure how well a clustering recovers these known classes. Or in topic modeling, if we have category labels for documents, we can gauge how well an unsupervised method rediscovered these categories.

When to use external metrics

External metrics are typically employed when:

- Partial ground truth is available: E.g., we have "true" classes or labels for a subset of data.

- Controlled experiments: E.g., we artificially generate labeled data to test or validate clustering algorithms.

- Benchmark datasets: E.g., we run multiple clustering algorithms on standard data like MNIST digits with known digit labels, using external metrics to see which algorithm best recovers the reference labeling.

Of course, if the external reference does not genuinely reflect the structure we want, or is noisy, the evaluation can be misleading. In practice, external metrics are often used as an initial or partial check, supplemented by internal metrics and domain-specific analysis.

Rand index

The Rand index (Rand 1971) is one of the earliest and simplest external metrics. It operates on pairs of data points:

- : The number of pairs that are in the same cluster and the same class.

- : The number of pairs that are in different clusters and different classes.

- : The number of pairs that are in the same cluster but different classes.

- : The number of pairs that are in different clusters but the same class.

The Rand index is:

It ranges from 0 to 1, where 1 indicates a perfect match between the predicted clusters and the external labels, and 0 indicates a complete mismatch (in the sense of pairwise relationships). Because of the way it counts pairs, the Rand index might be biased toward certain solutions in high-dimensional or large-scale scenarios where many pairs exist.

Adjusted Rand index

The Adjusted Rand index (ARI) was introduced to correct for chance groupings in the Rand index. The ARI can take on negative values if the index is lower than the expected value under random labeling, and it is 1 for a perfect match. One common formulation:

where:

- is the number of points in both reference class and cluster .

- is the number of points in reference class .

- is the number of points in cluster .

- stands for the binomial coefficient "n choose 2."

ARI is widely used because it corrects for label permutations and random chance, making it more robust than the raw Rand index. In many empirical studies, ARI is favored as the default measure if external labels are known.

Mutual information based metrics

Another family of external metrics is grounded in information theory, measuring how much mutual information exists between the cluster assignments and the external labels. Common variants include:

- Normalized Mutual Information (NMI)

- Adjusted Mutual Information (AMI)

- Variation of Information (VI) (which can also be used to measure dissimilarity)

The general idea is that if the clustering assignments convey much of the same information as the external classes, the mutual information is high. NMI normalizes this quantity to avoid biases from label set sizes. AMI further adjusts NMI to account for random labeling.

For instance, the Variation of Information is:

where is the joint distribution of cluster and class , while and are the marginal distributions. Variation of Information can be interpreted as the sum of the information lost and gained when moving from one partition to another. Unlike mutual information-based measures that might be bounded by [0,1], VI naturally ranges from 0 to , though it is often used in a relative sense.

Fowlkes–Mallows index

The Fowlkes–Mallows index (FM) is computed as:

where , , are the same terms as used in the Rand index definition. The FM index effectively measures the geometric mean of precision and recall in the context of pairs of points, making it akin to the F1 measure in supervised classification. Higher FM indicates better alignment with the external labeling.

Other external metrics

Besides the widely used ones above, numerous other external cluster validity measures exist, such as:

- Jaccard index: Focuses on how many point-pairs are in both the same cluster and same class but disregards those in different classes and different clusters.

- Hubert's statistic: Summarizes average distance relationships between points across different clusters.

- Phi Index: A correlation-like statistic measuring how pairs are distributed in the cluster and class partitions.

- Purity: Aligns each cluster with its majority class and measures the proportion of correctly assigned points.

- F-measure (in an external context): Summarizes precision and recall for each cluster-class combination, then aggregates them with respect to cluster or class size.

Practitioners often select external metrics that best match the nature of their external labels. For instance, if they want to give partial credit for overlapping classes, they might use mutual information-based measures. If they want a measure akin to accuracy in classification, they may prefer Purity or ARI.

Model selection and evaluation

Selecting a proper metric is essential for model selection and evaluating clustering results. In practice, one typically cannot rely on a single measure. Instead, one either chooses:

- Internal metrics only: When no labeled data is available. The user might compute Silhouette, Davies–Bouldin, or Calinski–Harabasz indices for different numbers of clusters or different parameter sets, then choose the parameter set that yields the best average internal index performance.

- External metrics only: When a labeled dataset is available and the external reference is considered reliable. One might try ARI, NMI, or Fowlkes–Mallows.

- Hybrid approach: Sometimes partial labels or partial structure is known, or domain constraints exist (e.g., known subpopulations). The user might combine external metrics with internal ones to glean more insights.

Balancing bias and variance in clustering

Though we often talk about bias–variance trade-offs for supervised models, the same concept has an analogue in clustering:

- High bias: If the clustering method or metric is too restrictive in the shapes or patterns it can detect, it might produce oversimplified solutions. For instance, K-means might enforce spherical clusters.

- High variance: If the clustering is too flexible or sensitive to noise (e.g., picking too many clusters or being extremely reactive to outliers), it might produce partitions that overfit idiosyncrasies of the data.

Metrics themselves can push an algorithm to either simpler or more complex partitions. For example, SSE might keep decreasing by adding more clusters, so if we only track SSE, we might be misled to use an unreasonably large number of clusters. Meanwhile, a measure like Silhouette or Calinski–Harabasz might plateau or decrease after a certain , giving a more balanced sense of the best partition.

Interpreting metrics in a practical setting

Clustering metrics should not be interpreted in isolation. For instance, a Silhouette of 0.60 might be acceptable in one domain but subpar in another domain with a different data structure. Domain context matters a great deal:

- Data geometry: Are clusters spherical, elongated, manifold-based, or shape-based (e.g., concentric rings)? Many of these metrics assume spherical or convex clusters.

- Data scale: Are we dealing with thousands of points or millions? Some metrics might be computationally infeasible.

- Noise: Datasets with heavy noise or outliers can drastically affect metrics like SSE or DB index.

In short, metrics can guide model selection and hyperparameter tuning, but an interpretative lens is always required. Real-world tasks sometimes weigh other constraints (like interpretability or the meaningfulness of clusters to domain experts) over purely numeric scores.

Advanced considerations

Below are a few advanced considerations that frequently arise in modern clustering tasks, especially as data complexity grows:

Handling high-dimensional data

In very high-dimensional spaces (such as gene expression data with tens of thousands of features or word embeddings of large vocabulary in NLP tasks), distance metrics like Euclidean distance can become less meaningful. This phenomenon, known as the Curse of dimensionality, might distort the differences between inter-cluster and intra-cluster distances, making many indices unreliable.

- Dimensionality reduction or feature selection is often recommended before clustering.

- Distance-based metrics such as Silhouette or Davies–Bouldin may become less interpretable.

- Density-based metrics (like those used for DBSCAN) can also degrade in performance if distances saturate.

In these scenarios, domain-driven transformations, principal component analysis (PCA), or other specialized approaches may be required.

Stability of clustering solutions

Another way to evaluate or compare clusterings is to assess stability: If the clustering solution is robust, small perturbations in the data or random initializations should not cause the partition to change drastically.

- One approach is bootstrap-based stability: Repeatedly sample the data, cluster it, and measure some notion of consistency.

- Another approach is to measure how well the same metric (e.g., silhouette) changes across random seeds. If a particular cluster structure is stable, the metric might remain fairly constant.

However, stability alone does not guarantee correctness for complex or multi-modal data. It is still an important factor in deciding if your chosen or cluster structure is robust.

Domain-specific metrics and constraints

In certain fields, domain-specific constraints redefine "distance," "similarity," or the notion of "correct" partition:

- Text clustering might rely on specialized similarity measures (e.g., cosine similarity in TF-IDF space).

- Spatial clustering in geosciences might factor in geographical adjacency constraints.

- Graph-based clustering might revolve around modularity or community detection metrics.

Domain knowledge can alter or even override standard metrics when specialized structures or relationships exist. Hence, in advanced real-world scenarios, it is common to define custom metrics that incorporate domain constraints.

Pitfalls and common mistakes

- Overinterpreting metric values: Seeing a "good" value of Silhouette (e.g., 0.7) does not automatically confirm that the clusters discovered are meaningful for the domain use case.

- Ignoring domain context: This can lead to clusters that are mathematically "clean" but worthless in a practical sense.

- Misapplication to unstructured data: For example, using Euclidean distance-based metrics on text data without proper embeddings or transformations can yield misleading results.

- Excessive complexity: If the metric is extremely complicated or has many hyperparameters, it might be prone to overfitting or might produce results that are themselves hard to interpret or replicate.

Implementation examples

Below is a simple Python demonstration showing how to compute some of these metrics using scikit-learn and related libraries. This code snippet is not exhaustive but illustrates the practical usage of popular measures like Silhouette, Calinski–Harabasz, and Davies–Bouldin. We will also demonstrate the Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) in an external metric context.

import numpy as np

from sklearn.cluster import KMeans

from sklearn.datasets import make_blobs

from sklearn.metrics import silhouette_score, calinski_harabasz_score, davies_bouldin_score

from sklearn.metrics import adjusted_rand_score

# Generate synthetic data

X, y_true = make_blobs(n_samples=1500, centers=4, cluster_std=0.6, random_state=42)

# Let's try K-Means with different numbers of clusters

for k in range(2, 6):

kmeans = KMeans(n_clusters=k, random_state=42)

labels = kmeans.fit_predict(X)

# Internal metrics

sil = silhouette_score(X, labels)

ch = calinski_harabasz_score(X, labels)

db = davies_bouldin_score(X, labels)

# If we treat y_true as external labels, we can measure ARI

ari = adjusted_rand_score(y_true, labels)

print(f"K = {k}:")

print(f" Silhouette Score: {sil:.4f}")

print(f" Calinski-Harabasz Score: {ch:.4f}")

print(f" Davies-Bouldin Score: {db:.4f}")

print(f" Adjusted Rand Index: {ari:.4f}")

print("===================================")

From this snippet, we can observe how each metric behaves as changes. For instance:

- The Silhouette Score might peak at the "correct" number of clusters.

- The Calinski–Harabasz Score generally increases with better separation.

- The Davies–Bouldin Score is best when minimized.

- The Adjusted Rand Index only makes sense if we assume that y_true is a valid reference labeling. It typically peaks where the cluster structure aligns best with the ground truth.

Visualizing clusters and their metrics

Beyond numeric metrics, data scientists frequently rely on visual tools:

- Elbow method: Plot SSE (within-cluster sum of squares) for different . We look for an "elbow" or a diminishing return.

- Silhouette plot: Visualizes how each sample's Silhouette value changes.

- Cluster scatter plots or PCA: Even if data is high-dimensional, one can use dimensionality reduction or embedding to visualize cluster separation.

These visual diagnostics often go hand-in-hand with the numeric scores to yield a deeper understanding of the clustering.

Conclusion

Clustering metrics are indispensable in any unsupervised learning workflow. Because clustering is inherently subjective without a labeled ground truth, these metrics serve as proxies for "goodness" or "quality." They can highlight features like compactness, separation, and alignment with external labels or domain knowledge. Nonetheless, no single metric — nor even a set of metrics — can completely replace domain insight and critical reasoning about how well the clusters match real-world needs.

Main Takeaways:

- Internal metrics (Silhouette, Davies–Bouldin, Calinski–Harabasz, etc.) measure cohesion and separation based solely on data and cluster labels.

- External metrics (Rand, Adjusted Rand, Mutual Information measures, Fowlkes–Mallows, Jaccard, etc.) leverage known external labels or references to quantify agreement.

- Practical usage typically involves computing multiple metrics, understanding their assumptions, and integrating domain knowledge to ensure that clusters are meaningful.

- Advanced research has proposed numerous specialized or computationally efficient indices (e.g., S, Dunn variants, Score Function, etc.). The choice often depends on dataset size, shape, and the clustering algorithm.

- No single best solution exists — the right metric is problem-dependent, and the best practice is to confirm the clustering solution from different perspectives.

I encourage you to experiment with a variety of clustering metrics and always remain skeptical of a single numeric score. Clustering is both an art and a science, and metrics are the scientific tool that, combined with domain-specific wisdom, lead you to robust and insightful groupings of your data.

References for further reading (not exhaustive):

- Arbelaitz and gang, "An extensive comparative study of cluster validity indices," Pattern Recognition, 2013.

- Bezdek, J. C., "Numerical taxonomy with fuzzy sets," Journal of Mathematical Biology, 1974.

- Halkidi, M., Vazirgiannis, M., "Clustering validity assessment: finding the optimal partitioning of a data set," Proceedings of the 2001 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining.

- Hubert, L., Arabie, P., "Comparing partitions," Journal of Classification, 1985.

An image was requested, but the frog was found.

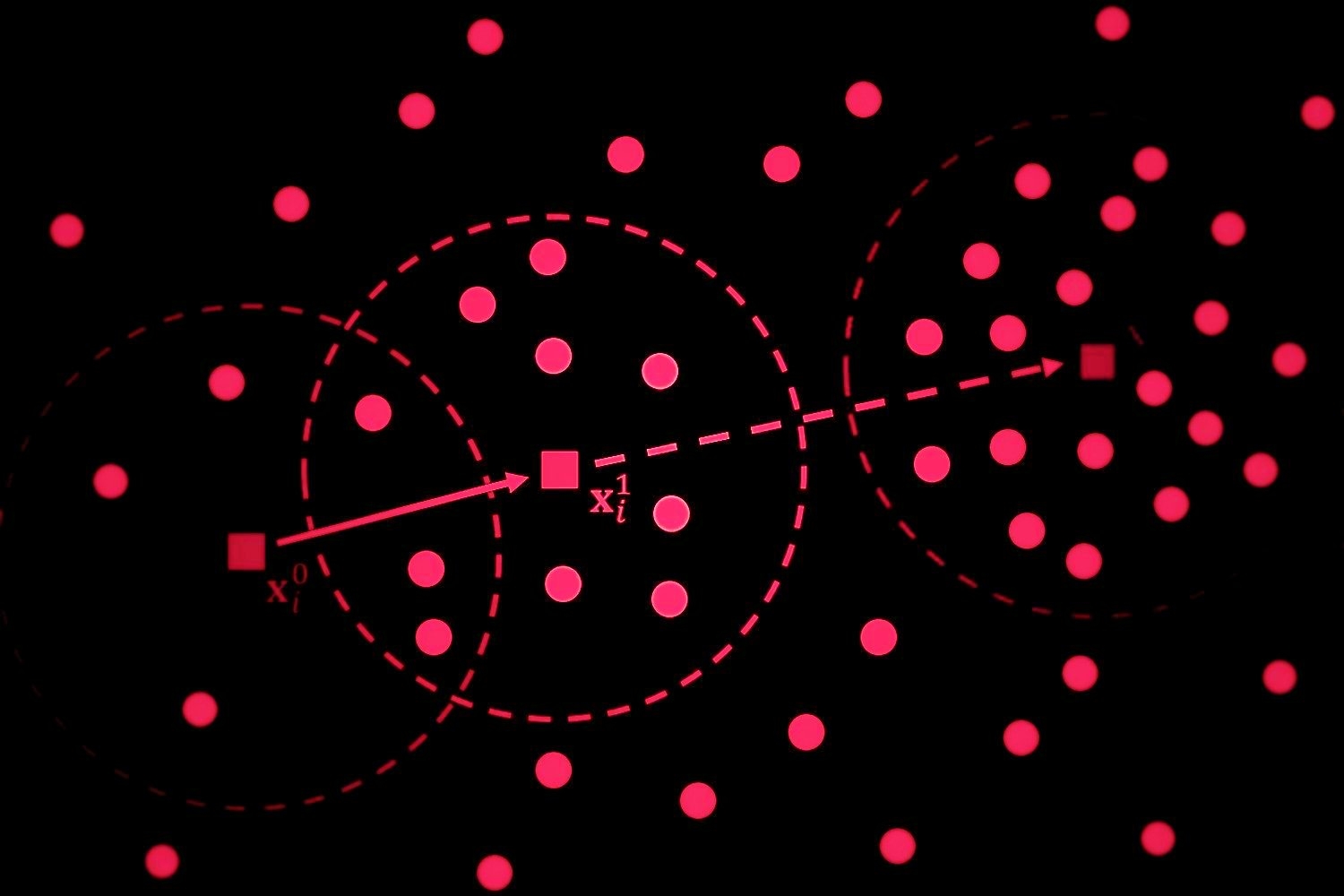

Alt: "two-cluster-example"

Caption: "Visual representation of two clusters. Goodness depends on cohesion and separation."

Error type: missing path

Ultimately, the best approach to evaluating clustering is to combine multiple quantitative measures, domain knowledge, and exploratory visualization. This synergy typically leads to solutions that are not only mathematically sound but also practically useful.